160 Years, Part IV: The enlightenment of Black History

February 28, 2019

From slavery and religious oppression, to disrupted childhoods, much of Black History has been marred with misfortune and pain. Consideration must be given, however, to not only the tragedies, but also the triumphs of such an enduring race.

In this final feature for the last day of Black History Month 2019, I wish to end on a high note, to give precedence to groundbreaking achievements of the African-American diaspora.

In this final feature for the last day of Black History Month 2019, I wish to end on a high note, to give precedence to groundbreaking achievements of the African-American diaspora.

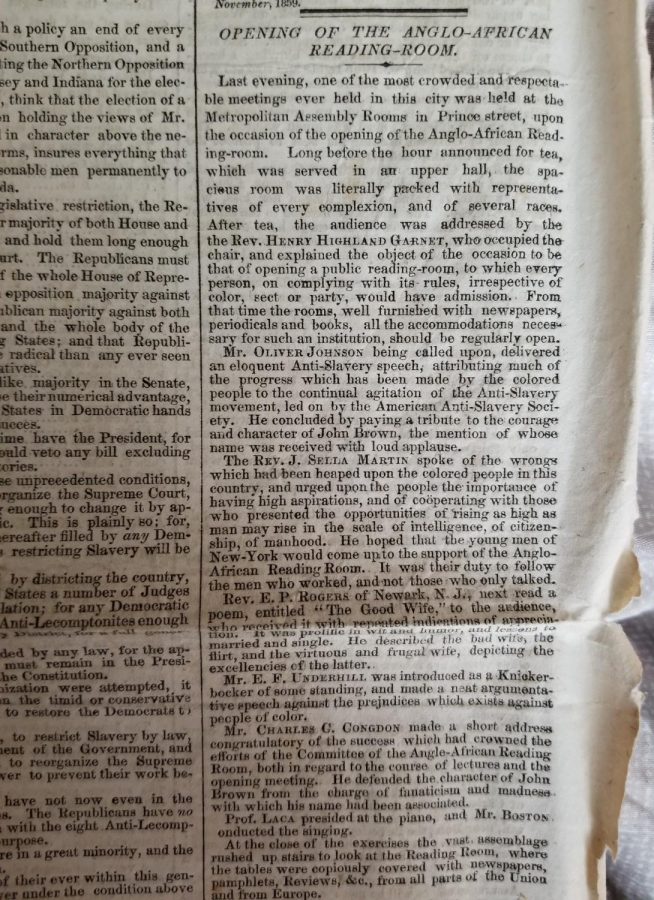

In the Nov. 11, 1859 edition of the New York Daily Tribune, I found an article about the opening of the Anglo-African Reading-Room on Prince Street in New York city. The article detailed the ceremony at the Metropolitan Assembly Rooms:

“Long before the hour announced for tea, which was served in an upper hall, the spacious room was literally packed with representatives of every complexion, and of several races. After tea, the audience was addressed by the Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, who occupied the chair, and explained the object of the occasion to be that of opening a public reading-room, to which every person, on complying with its rules, irrespective of color, sect or party, would have admission.”

Perhaps best described as one of the most profound abolitionists that modern America does not know about, Garnet was at the forefront of the anti-slavery movement of the 19th century, progressing from childhood slave to founding president of the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society. In fact, he gave one of the most famous and impactful speeches of his lifetime right here in the Queen City.

On Aug. 15, 1843, at the National Negro Convention in Buffalo, Garnet delivered an address to slaves known as the “Call to Rebellion” speech (I highly recommend listening to a modern narration of the speech in its entirety here). He encouraged bondmen “to use every means” to rebel against their masters while emphasizing the ungodliness and immoralities of the oppressed descendants of Africa. In other words, he was Malcom X about 70 years before Malcom X was even born.

Garnet was not the only speaker at the Anglo-African Reading-Room’s opening, however, nor was he the only one with Buffalo ties.

The Tribune article tells of another key figure present during the night’s festivities who also delivered an important message:

“The Rev. J. Sella Martin spoke of the wrongs which had been heaped upon the colored people in this country, and urged upon the people the importance of having high aspirations, and of cooperating with those who presented the opportunities of rising as high as man may rise in the scale of intelligence, of citizenship, of manhood.”

Like Garnet, John Sella Martin was also born into slavery. In 1856, however, he forged freedom papers and made his own way out of slavery to become an influential orator and abolitionist. Two years later, he would move to Buffalo to become reverend of the now-historical Michigan Street Baptist Church, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places and “was often the last stop for fugitive slaves on the Underground Railroad before crossing over to Canada,” according to the church’s website.

Other attendees spoke at the opening of the reading room as well, including reformer and abolitionist Oliver Johnson, an “editor and writer for every antislavery newspaper in America” during his time.

One key detail the Tribune failed to mention is the significance of the reading room in its day. In a country mired by slavery and segregation, an establishment for people of color to be able to freely seek enlightenment was beyond an accomplishment; it was a symbol of victory and establishing identity.

Sadly, the Anglo-African Reading-Room seems to be all but erased from history, but it was one of many unsung developments that set the precedence for African-American culture.

The development of African-American libraries, museums, colleges/universities and other historical establishments transformed from products of segregation to products of celebration. Black History is neither divisive nor exclusive. Black history was all we had because it was all we were given, which is why it should and will always be celebrated.

By looking through articles of newspapers from the 1800s, I became enlightened about my own history and grew more inspired and determined to prove that Black History and the future thereof are not connected by chains, but by parallels; although this has led to some unfortunate circumstances, the parallels themselves are not.

Links between our past and present serve as gifts to our futures if we dare be inspired from our reflections instead of oppressed by them. Hopefully, these treasures will be discovered by and embedded into the future of Black History and all mankind, that we never repeat our shortcomings and that we always improve on our successes.

This is the finale of a 4-part series; the rest remains unwritten.