160 Years, Part III: Black History and the invisible children

February 21, 2019

At-risk. Troubled. Underprivileged. Such are the adjectives commonly used to describe many black boys and girls in America. As seen throughout history, the African-American voice has been silenced and misarticulated; even more muffled have been the screams and protests of African-American children, both within and outside of their communities.

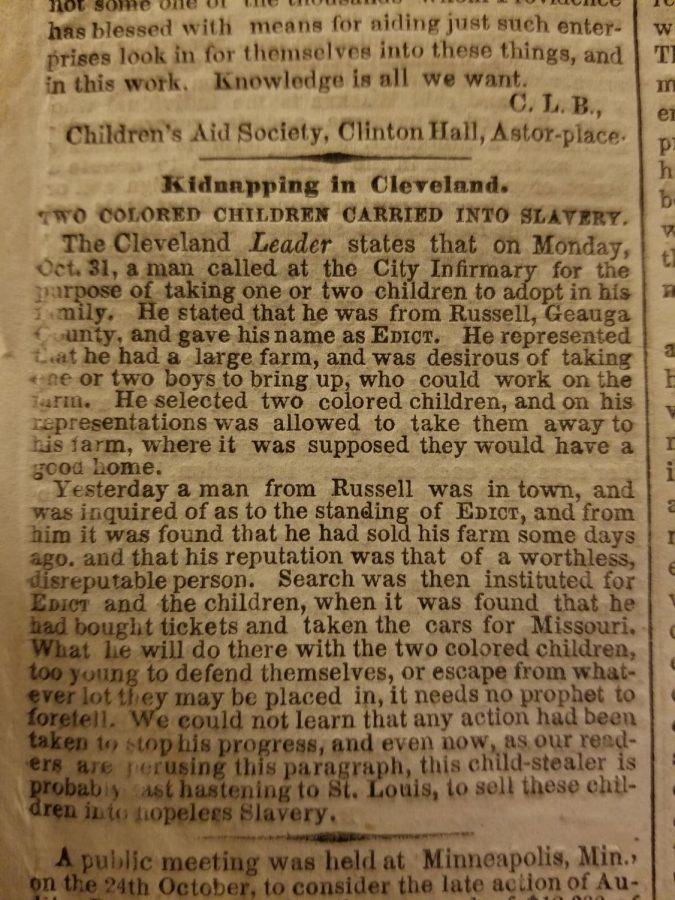

This week’s journey to the past comes by way of The New York Times’ Nov. 5, 1859 edition.

A short article, “Kidnapping in Cleveland,” tells the story of two black boys—presumably ill or disabled, as they were housed in an infirmary—who were promised good lives as farmhands, but instead were met with a different, utterly tragic outcome.

The story begins:

“[A] man called at the City Infirmary for the purpose of taking one or two children to adopt in his family. He stated that he was from Russell, Geauga County, and gave his name as Edict. …He selected two colored children, and on his representations was allowed to take them away to his farm, where it was supposed they would have a good life.”

Unfortunately, “Edict” not only failed to deliver on his promises, but he was proven as a “worthless, disreputable person” who sold his farm days prior and bought train tickets for himself and the boys to Missouri.

The fate of the boys was unknown, but certainly predictable:

“What he will do there with the two colored children, too young to defend themselves, or escape from whatever lot they may be placed in, it needs no prophet to foretell…even now, as our readers are perusing this paragraph, this child-stealer is probably hastening to St. Louis, to sell these children into hopeless Slavery.”

The heartrending tale and fate of these boys is by no means unique, even today.

In 2014, a photograph of a 12-year-old boy named Devonte Hart went viral when he was seen tearfully hugging a police officer at a Portland, Oregon protest against police violence. Four years later, his name was in the news once more—this time, under grim circumstances.

Last March, reports spread that Jennifer Hart, one of Devonte’s adoptive mothers, was intoxicated when she drove off of a 100-foot cliff in California, killing herself, her wife Sarah, and presumably all six of their adopted children (*four of the children’s bodies were found, but the bodies of Devonte and one of his sisters, Hannah, were never recovered. In fact, Devonte remains in the FBI’s Missing Persons database.)

Nearly a month after the incident, The New York Times published a story revealing the neglect and abuse suffered by the six children at the hands of their guardians.

The article exposed “cruel punishments” the Harts would inflict upon their children, including beatings, withholding of food and forbiddance of speaking (and even laughter).

Several of these incidents resulted in child welfare visits, but the only orders given were “in-home therapy, counseling and other “skill building activities.” The couple did, however, still receive “about $2,000 a month in adoption assistance.”

The Times article of last year tells a story not different from that of the Times article of 1859; many African-American children who are adopted out of the foster care system are brought into modern day slavery, suffering abuse while profiting their ‘caretakers.’*

As in the case of the Hart children, the dreadful stories of abused and neglected children are rarely heard until opportunities for interception and healing are no longer available. While we eventually hear stories like these about the voiceless children, however, the faceless ones are even harder to account for.

Data provided by USA Today from 2014 showed that of all missing children in America, African-American children were the most overrepresented, accounting for 33% of all reports, yet African-Americans make up only 13% of the entire U.S. population.

Oftentimes, distinctions are never made between runaways and abductees, but it needs no prophet to foretell what often happens to these youths. Casualties of human trafficking and the school-to-prison pipeline are disproportionately children of color and are oftentimes young men and women who either were abducted or tried to flee toxic home environments.

This leads to another grossly overlooked fact, that too often, home is the first hell of many African-American youths. Common sayings in the black community like “What goes on in this house stays in this house” or “Don’t put family business in the streets” lead to generational curses, denial of abuse and even demonizing of mental and emotional disorders. An environment that makes it taboo to confront and admit trauma can send just about anyone into the hands of new abusers, especially forsaken and impressionable youths.

Ironically, the invisible children only come into view when they are gone, either in terms of absence or death. For centuries, Black History has demonstrated how valuable yet endangered the lives of African-American children are. In order for healing and change to take place, the paradigm must shift.

This is why representation matters. This is why #blackgirlmagic and #blackboyjoy deserve as much attention as #bringbackourgirls. Most importantly, this is why we must love, value and protect our children at all costs. Silence is not golden when you don’t have the courage or willingness to speak up.

*Disclaimer: I fully and completely acknowledge that many African-American children are adopted into loving families. The incident of the Hart family is one that happens to unfortunately reflect many others.

This is Part 3 of a 4-part series; stay tuned for the last installment next Thursday. It will enlighten you.