160 Years, Part II: Black History and religious progress

February 14, 2019

Finding God in a god-forsaken life—such has been the foundation of survival for generations of Africans/African-Americans. Without a doubt, God looks different than in the past: to some, God is The Father, to others, the universe, still others, an interpretation of our higher selves. Some are certain there is no god; some are certain they can’t be certain.

Relevance of my saying all of this? Religion and perceptions of God are ever-evolving; one constant throughout history, however, is no other demographic cleaves to the divine like the African-American population.

I found in my archive of vintage newspapers a very interesting story by way of The Examiner from Sept. 8, 1892.

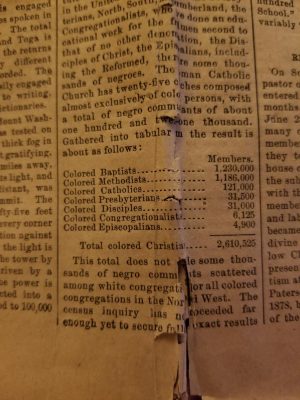

The “Pulpit and Pew” section contained an excerpt of a 10-page report by H.K. Carroll (1848-1931), an American scholar of religion and an editor of a New York-based weekly magazine called The Independent. The article, titled “Religious Progress of the Negro,” contained statistical data for the African-American population, development of religion among various demographics and plenty of unsavory opinions.

The article begins as so:

“If the genus man is a religious being, the species negro is pre-eminently so. Wherever you find him, in whatever state of civilization, whether living as a savage in the depths of the Dark Continent or as an educated and prosperous citizen of the United States, you find him ever ready to acknowledge the claims of religion and attentive to its form.”

For the classification of his statistical collection, Carroll specified that the “negros” of which he reported consisted of full-blooded Africans, as well as “mulattos, quadroons and octoroons;” those who had half, quarter, and eighth percentages of African ancestry, respectively (As an aside, this is an interesting example of the historic use of the “one drop rule.”).

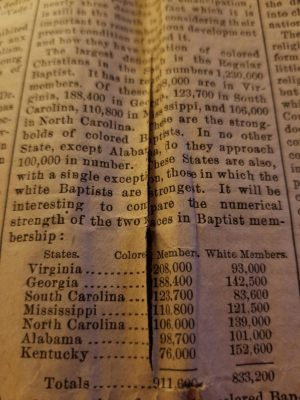

In analyzing churches of several Southern states, Carroll found the number of “colored members” either rivaled or outnumbered those of “white members.”

In analyzing churches of several Southern states, Carroll found the number of “colored members” either rivaled or outnumbered those of “white members.”

These findings were likely (and should still be) unsurprising to most. Among suffering separations of families, murder, many forms of unimaginable torture, tremendous labor and exclusion of rights, those of African ancestry owned nothing but the divine promises of salvation and life everlasting.

Carroll’s interpretation of “religious progress,” however, challenged the ties of Africa’s descendants with faith.

He made this conclusion of “religious progress:”

“The common idea respecting the negro’s religion is that it is a crude and superficial form of Christianity and exercises but little moral influence upon his life. He is religious, intensely religious, many insist, but he is not moral.”

Furthermore, he described the religious origins of Africans before slavery as “crude notions of African savagery concerning witches and evil possessions and using strange ceremonies to ward off bad spirits.”

In giving a generic and misinformed description of ancient African voodoo practices (which also  consisted of medicine, agriculture and ancestral honoring) and in omitting the continued practice of Islam among some Africans (which has close ties to Christianity) and the fact that much of Christianity has roots in African regions, the argument made for “religious progress” demeaned the spirituality Africans already possessed before they were brought to America and enslaved.

consisted of medicine, agriculture and ancestral honoring) and in omitting the continued practice of Islam among some Africans (which has close ties to Christianity) and the fact that much of Christianity has roots in African regions, the argument made for “religious progress” demeaned the spirituality Africans already possessed before they were brought to America and enslaved.

To first establish religious freedom, the most basic of freedoms had to be obtained. Oftentimes, African-Americans were not allowed to equally partake in, or even preach, the very gospel in which they had faith.

Carroll noted that the development and racial integration of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1845 included segregating churches, pews and galleries, as well as “establishing missions among plantation negroes, and appointing its own white ministers to preach the Gospel to them[.]”

While religion was used to mark “progress” of African-Americans, it was also used to measure injustices held against them.

Take, for instance, a story from New-York Daily Tribune (Feb. 11, 1860). A writer identifying only as “An Old Republican” called into question the contradiction of his state’s values and its pride in slavery in the article, “Is Slavery Unjust? –Virginia Testimony.”

An excerpt reads:

An excerpt reads:

“[W]hile we adjured the God of Hosts to witness our resolution to live free or die, and imprecated curses on their heads who refused to unite with us in establishing the empire of freedom, we were imposing upon our fellow-men, who differ in complexion from us, a Slavery ten thousand times more cruel than the utmost extremity of the grievances and oppressions of which we complained.”

The writer’s sentiment was a plea of righteous indignation against the South, an acknowledgement that despite “the blessings which the Almighty hath showered down upon these States,” America had become “the vale of death to millions of the wretched sons of Africa.”

Nearly two centuries and many freedoms later, there are some consistencies (in statistical figures, anyway) with The Examiner’s article.

The preeminence (as Carroll mentioned) of religious dedication among African-Americans remains even today: survey data from Pew Research Center shows that more African-Americans subscribe to religious denominations, cite religion as “very important,” pray daily and attend more religious services than any other ethnic group in the nation.

Also consistent with Carroll’s findings are, among the African-Americans who belong to some division of the Protestant faith, most are Baptists, also, there are very few African-Americans who identify as atheist or agnostic. (*Compare Carroll’s report with the Pew Research Center’s data).

True religious progress, however, exists today in modern denominations and spiritual practices. Historically black churches continue to thrive and evolve in modern America, as well as ideas of spirituality. Islam, Judaism, Jehovah’s Witness, Buddhism and other denominations all have percentages of African-American devotees as well.

Faith or no faith, the imprint that religion has left on the African/African-American community has extended far beyond the church and can be denied by no one. ‘Old negro spirituals,’ ring shouts and hymns derived country, blues, jazz and other great and uniquely American music genres. Familial structure was born from the structure of the congregation. Sermons, psalms and prayers birthed some of the earliest African-American poetry, lyrics and literature. From the cotton fields to “the culture,” the role of religion in Black History has, and will continue, to shape not only the African-American community, but the entirety of the nation.

This is Part 2 of a 4-Part series; next Thursday: Two Black Boys. Stay tuned.