Longtime Buffalo State professor leaves lasting legacy

Donald O’Brien remembered for work in classroom, at home and on the field

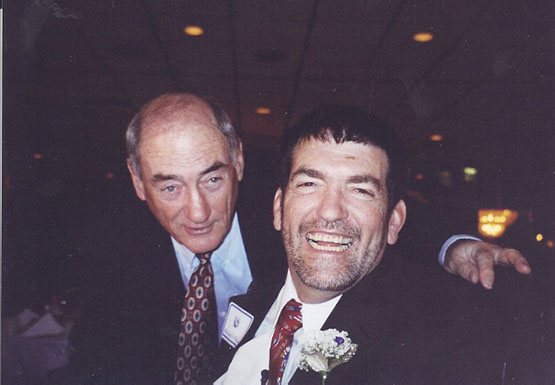

Photo courtesy of Donald O’Brien’s family

Donald O’Brien and his son Mike, for whom O’Brien served as primary caretaker.

It’s 1951, and the first half of Donald O’Brien’s night shift at the Pepsi-Cola bottling plant is winding down. He clocks out, punching his time card before going on his dinner break, about an hour and 45 minutes long.

Punch out.

But Don didn’t use his dinner break for dinner. Well, actually, he did — the other fighter was his dinner. He ate him up in the ring, knocking him out cold for the Golden Gloves middleweight championship title.

Punch out.

Check the clock: Don still has an hour left on his dinner break. Back to work. His professional baseball career was not a year-round job, and Golden Gloves boxing doesn’t put bread on the table. He only fought for the gold watch awarded to the winner. He got the watch. Now he’s got to make a living.

Punch in.

•••

The job at the plant didn’t last long, and neither did the boxing. Don left school and everything else behind when he was 17 to play professional baseball, and the spring after the Golden Gloves fight, he was fighting for a roster spot in the St. Louis Cardinals’ organization.

The catcher with the pull-power swing and the strong arm made the cut because he hit a home run, a long towering shot, to the opposite field off of a pretty good pitcher. He wouldn’t hit another opposite field homer until he was well into his 50s, playing MUNY ball in Buffalo while directing the reading clinic and teaching elementary education at Buffalo State.

Don played four seasons in the minors, with the Cardinals’ and Detroit Tigers’ low-level affiliates. He never made the majors, but he made a name for himself, nearly drilling Cardinals legend Stan “The Man” Musial with an errant throw during a game of catch at spring training.

“You better watch out,” Musial said, half-joking. “You hit me, and they’ll send your ass to Class D Paduca!”

•••

Winnipeg, 1954, the second game of a doubleheader.

Don had three hits in the first game, and paid for it in the second, hit by a pitch thrown way inside. The pitcher plunked him, so he went out to the mound and plunked him back, casually walking over to first base after landing his haymaker to watch the subsequent brawl. He had already done his part.

He also broke his hand on the punch, couldn’t hit or throw because of it, and was released the next day. Before heading home to Buffalo he signed with a team in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, making more money than he had with Winnipeg.

So Don breaks his hand on an opposing pitcher’s face and ends up in Weyburn, of all places. It was there, in Weyburn, while pumping gas, that he met Vivian for the first time. They got married a year later.

Punch out.

•••

1955. After marrying Vivian in secret (Catholics and Protestants weren’t supposed to get married to each other back then), Don and his wife chased his pro-ball dream together, first to Virginia and then Jamestown, where he was released. They moved back to Buffalo, Don completed his high school equivalency in 1956, and then graduated from Buffalo State in three years.

Shortly after, he and Vivian started a family. Colleen was born first, then Pat, then Mike, each a year apart, then Cathleen and Terrence later.

Three days after he was born, Mike contracted double pneumonia and developed a hernia from coughing. During surgery to remove the hernia, his heart stopped beating, creating the cerebral palsy.

He can’t walk, can’t stand on his own. He can type, but it takes him a long time. He needs help feeding himself, bathing and going to the bathroom.

Don and Vivian devoted their lives to caring for Mike. They made sure he was never left out of anything.

When Don had a game, Mike would keep score and track pitch locations. When the kids played hockey on open courts or frozen ponds, Mike would play in net, waving around the goalie stick he received from former Buffalo Sabres’ goalie Roger Crozier after a game once. When they played baseball, he’d be the pitcher’s mound, and they’d play pitcher’s mound out, throwing the ball towards him instead of first base.

Don bought a van just for Mike. It was blue. Don fixed it up, added a wheel-chair lift. When the family went on a trip to Disney, Mike went with them. Everyone wore matching tie-dye hats and tee shirts.

In between teaching high school during the day and taking classes at night to complete his masters and his doctorate, Don would wake up early in the morning and take care of Mike. Help him use the bathroom, shower him while Vivian picked out Mike’s clothes, then dress him. When he got back from work or school, he’d help put him to bed, turn him over, sit with him if he was sick, blow Mike’s nose when he couldn’t do it himself.

Don left his high school teaching job to become an associate professor of elementary education at Buffalo State. In 1982, he became a full professor. Now he could pick what days he went in to teach. But he was still a busy man.

He refereed high school football, played a lot of golf, and went out with his friends for a nightcap occasionally. He won a lot of awards, for his devotion to sports and to his community and to his college. He was a founding member of the Western New York Baseball Hall of Fame, and was inducted himself in 1998.

He did it all while raising his kids, while taking care of Mike — with a whole lot of help from Vivian, of course.

Don still played baseball well into middle age, three nights a week, and softball two nights a week, plus weekend tournaments. He still had that pull-power. Once, while playing at Delaware Park, he knocked out his third base coach with a foul ball.

Punch out.

•••

Don’s son Pat handles the family’s business now. He was a star athlete at Kenmore East, played quarterback at Yale and now works at an economic development corporation in Milwaukee.

Mike still lives at home. Don and Vivian used to split up the duties, but now only Vivian is left to take care of him, and she’s too old to be her son’s main caregiver.

They hired a few nurses, got some help from the state. Mike gets out of the house every so often to go to art classes provided by a disability services agency.

The nurses have specific days that they come. Pat and Vivian are still working on covering the days they don’t come.

Finding housing for Mike isn’t easy. Pat says there are about 2,700 beds in homes for the developmentally disabled, but they’re all full, and there’s a waiting list of about 900 people for the ones that open up.

900 people.

So, Pat reasons, if everyone in those 2,700 beds lives to be about 50, then that means the wait is about 45 years for everyone on the list.

Mike is 55 years old. He’s still waiting.

•••

Punch in, punching.

Punching: Don’s father, Ray, did a lot of that in the circus.

Ray was an All-State end during his football days in Minnesota — back when they played both ways — and an All-State mile runner, too. In 1919, when the Great Farm Depression hit, Ray left his rural Midwest home and joined the circus, where people lined up to try to knock him out and win a $5 prize.

No one ever knocked Ray out. He was a good boxer, but he was smart, too, and if someone stepped up looking like trouble, he’d slip them a dollar or two and they’d take a fall.

But Ray couldn’t do that forever, and he didn’t want to. So he left the circus in Florida, just didn’t catch the train on its way out of town, and worked his way up the east coast. He boxed some more, fighting in Rochester, Albany, even Boston, before settling down in Buffalo, where Don was born.

Ray taught Don the right way to play the game, the right way to live. They didn’t have much money — Ray was a cabbie and Don’s mom ran a hot-dog stand — but as Ray often told Don, “There are a lot of ways to be rich.”

•••

It’s 2013, late August, the dog days of summer for pro baseball teams.

Don’s sick — he has carcinoid cancer. He’s at his home, tucked away in a Tonawanda cul-de-sac, the family home since 1964. There’s a wooden backboard with a rusty basketball rim hanging on the garage over the driveway.

Don’s dying. He’s surrounded by people he loves: Pat and Vivian and Mike and the rest of his immediate family.

He gathers up the strength to speak for the last time.

“It’s been wonderful,” Don says. “You are all wonderful. I love you all.”

Punch out.

Leif Reigstad can be reached at reigstad.record@live.com or on Twitter @LeifReigstad

Http://siteplancul.info/ • Feb 12, 2014 at 7:46 am

Hello, just wanted to say, I loved this article.

It was helpful. Keep on posting!