VICE looks at federal prison system

October 13, 2015

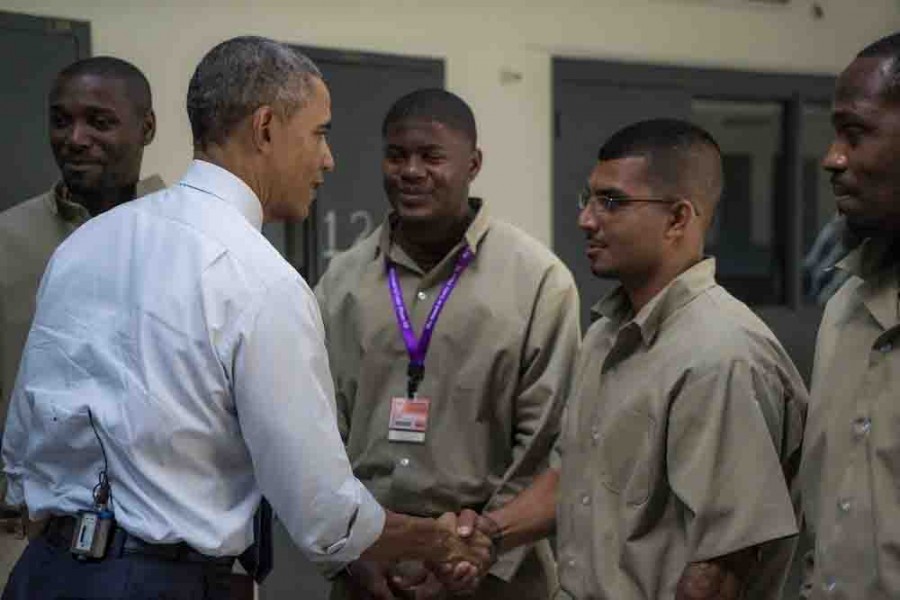

Fixing the System documents President Obama’s unprecedented visit to a federal prison. Obama met with six inmates to discuss the reasons behind their incarceration and what can be done to improve the criminal justice system. Shane Smith, the director of Fixing the System, conducted interviews with Obama, former Attorney General Eric Holder, judiciary and community reformers, and various federal prisoners and their families, to show the interlocking elements of a criminal justice system that has gone awry.

It is a bleak portrait of a criminal justice system that incarcerates twenty-five percent of the world’s prison population through draconian sentences biased toward impoverished and non-white communities. These communities have been decimated by the void left by 1.1 million fathers that are currently incarcerated in America.

“If you don’t have a person teaching you the tools that you need to grow up to be a man, then quite naturally, you will be taken by the strength of gangs or the drug culture prevalent in our communities,” said one prisoner during an interview with Smith.

During his sit down conversation with six prisoners, Obama related his own struggles of growing up without a father, yet cited the support of his grandparents as a shield against the detriments that many urban youth face.

“I had more of a margin of error than a lot of children do who grow up in low-income communities that are surrounded by drug activities,” Obama said.

The documentary begins with the story of Bobby Stewart, a small business owner and father of two children who went into debt during the U.S. recession that began in December 2007. When Stewart could not pay back his loans, he was given drugs to sell in order to repay his debts. Stewart is now spending life in prison for charges of intention to distribute narcotics.

Bobby Stewart was locked up “the summer going into my senior year of high school,” said a weeping Latoya Stewart, his niece. “I graduated valedictorian. I went to college and graduated cum laude. Then I got my master’s degree. Five years ago I got married, and a year and a half ago, I had my first son. And for each one of those celebrations, Bobby’s name has been on the list. And what is so frustrating is that, a lot of my success I attribute to him, because he coached me along the way.”

We met Bobby Stewart’s brother, who has only spoken about Bobby “three times” because of the pain he feels in his brother’s absence.

“Our father ran this engine shop, and then Bobby and I ran it. When the recession hit, we needed money and Bobby made some poor choices. I don’t understand how he can never come back though. That’s not helping him.”

Smith visited prisons across the United States and found that the commonality for all prisoners was the pain of being separated from their families.

“Even though I am in prison, my fathering obligations don’t stop,” said one prisoner who is serving a life sentence. “Whether it is a letter, talking to my son on the phone, or the few minutes I get to visit with him, I need to help him. If I get it wrong, where is his future, but where I am right now?”

Can a system that incarcerates people for the remainder of their lives be considered rehabilitative? Arnell Stewart, a twenty-seven-year-old prisoner from Denver, Colorado, cites the prison drug program as the means by which he found direction in life.

“It has taught me to recognize and accept the effect my behaviors have on my community and those around me,” Arnell Stewart said.

Arnell Stewart describes himself as a former “straight-A student and a nerd” before he became involved with drugs during high school. He cites the twelve-year absence of his mother and his father working “two or three jobs at a time” as part of the reason he became involved in the “wrong crowd.”

“Due to my criminal lifestyle and some of the successes I had education-wise, I felt like I couldn’t take advice from others because they weren’t as successful as me,” Arnell Stewart said.

The drug program that Arnell Stewart participates in teaches prisoners to identify thinking errors and patterns that lead to bad decisions.

“I found myself in prison,” Arnell Stewart said with religious zeal when Obama asked him if he attributed his critical thinking skills to a youth spent dealing drugs or the rehabilitation program which he participates in.

Fixing the System explores the systematic aspects that maintain America’s flawed criminal justice system. Holder believes the cycle of arrests, harsh sentencing, and broken communities which lead to more arrests, begin with a culture of “implicit bias.”

“We have the issue of police making an assumption about how likely it is that a young black man is involved in criminal activity simply because of the way he looks,” Holder said.

Judge John Gleason, the prosecutor famous for taking down mobster John Gotti, said because of mandatory sentencing statutes “injustice happens.”

“Only seven percent of drug-related arrests are made on managers or kingpins, yet the severity that Congress intended for those high-level drug dealers is being handed out to the other ninety-three percent,” Gleason said.

This “other ninety-three percent” are the small-time drug dealers emerging from low-income neighborhoods where education is sub-par, crime is rampant, job opportunities are low, and many households have an adult member who is incarcerated.

Smith bluntly asked Obama if the criminal justice system is racist, to which Obama carefully articulated that data shows that an African-American child is more likely to be suspended from school than a white youth for engaging in the same behavior, more likely to be arrested than his white peer for the same behavior, and more likely to get a stiffer sentence than his white peer for the same crime. These patterns of bias create a flawed criminal justice system that is self-perpetuating.

Brian Stevenson, a lawyer for the Equal Justice Initiative, argues that there is a “presumption of guilt” that follows non-white people into a courtroom. Stevenson is fearful of our country in that it is morally acceptable to sentence thirteen-year-old children to die in prison.

“We have a system of justice in this country that treats you much better if you are rich and guilty than if you are poor and innocent. Wealth, not culpability – shapes outcomes” Stevenson said.

As bleak as the landscape of justice appears in Fixing the System, there is great hope as well. Obama described his goal to end the requirement by employers that asks applicants to describe their criminal history before an in-person interview.

“If we can get you into the interview and you can tell your story, at least then you will have a fair chance at getting that job,” Obama said.

A bipartisan Congressional committee has put forth the “The Smarter Sentencing Act” with the intent to reduce the federal prison population by reducing the mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses.

“I think it was James Baldwin that said ‘there is nothing more dangerous than a man who has no hope,’” Senator Corey Booker said as he walked Smith through the most violent neighborhood of Newark, New Jersey and described his bipartisan participation in writing the “The Smarter Sentencing Act.”

As Obama said goodbye to the six prisoners he spoke to in the federal prison, they gazed in disbelief that a president, for the first time in history, had come to them. While it was only one small step off Air Force One for the president, it was a giant leap for a criminal justice system that has long neglected the plight of the impoverished and hopeless.

Stream VICE’s “Fixing the System” on HBO NOW

email: mccormick.record@outlook.com