Malik Campbell was The Greatest Athlete the City of Buffalo Has Ever Produced. But who is he now?

“Is Malik Campbell bound for the NFL or the NBA?”— The Buffalo News, 1995 …

… February, 2014.

The Record: A lot of people around here consider Malik Campbell one of the best athletes the City of Buffalo has ever produced. Do you agree?

Buffalo State men’s basketball coach Fajri Ansari: “Yes. Absolutely. He’s one of the few athletes I know that could just put the helmet up on Saturday and then go right to basketball practice on Monday.”

***

Malik Campbell, The Greatest Athlete the City of Buffalo Has Ever Produced, stands a few feet off the sideline talking to a reporter while the Buffalo State men’s basketball team practice on a frosty February evening, his long and slender body buried in a baggy black and gray sweat suit, a basketball tucked inside the crook of his right arm. Campbell, 36, still maintains the fantastic physical form that enabled him to excel in both basketball and football at Turner Carroll High School and, later, at Syracuse University in the late 1990s.

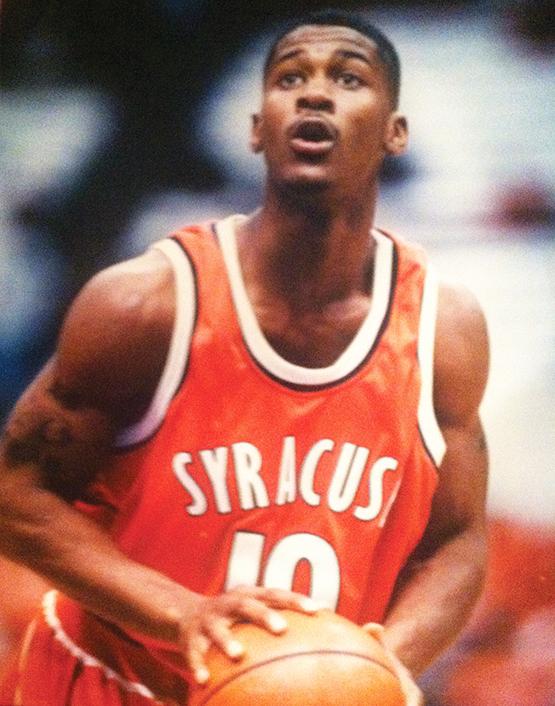

Malik Campbell playing basketball for Syracuse.

But those days are over, and now, Malik Campbell, the Greatest Athlete the City of Buffalo Has Ever Produced, is simply: Malik Campbell, Assistant Coach.

“Playing two sports at Syracuse was taxing,” Campbell says. “It was taxing on the body, it was tiring, but — ”

‘Lik!

A player shouts from across the court. Campbell responds, mid-conversation and without skipping a beat, by fluidly throwing the basketball he is holding in his right hand football-style; the ball traces a high-arcing path stretching a little less than the width of the gym and drops directly into the hands of the player patiently waiting on the other side. Malik Campbell, Quarterback.

“ — but I enjoyed it. It was a great opportunity and I wouldn’t turn it down for the world,” says Malik Campbell, Coach.

***

At practice, Campbell looks relaxed. He smiles and laughs with his fellow coaches and jokes around with the players. A Bengals’ player pulls up for a deep jumper and the defender doesn’t put a hand up in his face, and Campbell, beaming, shouts: “you just let him shoot that jump shot? You let him shoot the jump shot!”

Campbell deserves to have fun and to relax now. During his childhood he couldn’t afford to lose focus, not even for a minute.

Before Malik Campbell got to Turner Carroll, before he got to Syracuse, before he became Malik Campbell, The Greatest Athlete the City of Buffalo Has Ever Produced, and Malik Campbell, Quarterback and Malik Campbell, Point Guard and Malik Campbell, Coach, before all of that, Malik Campbell was just like most other 6-year-old kids growing up on Buffalo’s drug-and-crime ridden East Side. He played street football games and he fought.

“That’s all you knew,” Campbell says. “When I was growing up, if we lost, we fought. That was just what I did. You never wanted to be punked off, never wanted to be considered soft. That’s just what it was.”

Even then, Campbell had his eye on the pros. He looked up to the neighborhood stars, players like Trevor Ruffin (Bennett High School), who played two seasons in the NBA in the mid-90s, and Western New York’s all-time leading scorer Ritchie Campbell (Burgard).

While Malik’s neighborhood was a hotbed for rising athletic talents, it was also, for some, a sinkhole.

Example: the aforementioned Ritchie Campbell. He certainly had pro potential, but he didn’t have Division-I grades, so he floated around at a few community colleges before the street life sucked him all the way in. He served 17 years in prison for manslaughter. Growing up, Malik Campbell saw similar scenarios play out among his peers.

“I had friends get shot, friends get killed, friends go to jail at a young age,” Campbell says. “I never let that be my focus.”

“Most people from (Malik’s) block weren’t going to college,” Ansari says. “Most people were getting in trouble. He’s from the Ferry-Wohlers area, which was kind of notorious. Not everyone was getting scholarships in that group. The percentage was rare, especially (among) the African-American males from the East Side.”

But Campbell was rare — his talent, his drive. Even as a 6-year-old he hated to lose, and in street football and little league, he didn’t lose often. He only started playing basketball when he was 13 because that’s what everyone else was playing at the time, and everyone else was better than him, and he couldn’t stand it, so he kept playing, kept practicing, until, just like in football, he was better than everyone else.

Campbell’s father, a professional boxer, instilled in his son a strong work ethic and a stringent commitment to physical fitness.

“He’d wake me up in the morning and tell me to get up and go run, for no reason,” Campbell says. “I just always needed to stay in shape.”

Campbell saw his hard work pay off on the field and on the court, and soon, others started to notice, too. Word of Campbell’s talent eventually got around to Ansari, Turner Carroll’s head coach at the time, who had already turned the East Side school into a basketball powerhouse and was always looking for local kids who could play.

“Once I saw him play, I knew he was definitely a winner,” Ansari says.

But in Campbell, now a freshman, very much still remained of the street-hardened six-year-old scrapper. He’d get in fights during practice—once, Ansari remembers, Campbell took on a senior teammate—and he’d get called for technical fouls and was often kicked out of games.

“I was always a fighter, always been that way,” Campbell says. “Then as I got older, I couldn’t do that. I had to learn.”

Ansari, no stranger to working with players from tough backgrounds, would take Campbell aside, sit him down and talk with him, let him know what was wrong about what he did instead of yelling or getting angry whenever Campbell made a mistake.

“(Ansari) was like a second father,” Campbell says. “He mellowed me out. I was a little rough around the edges, had an attitude problem. His demeanor and attitude calmed me down a lot. He wasn’t the yelling type of coach. He was calm about everything, no matter how mad I was. That was him allowing be to be my own person, but understand the consequences behind (my actions). That helped me mature and become a better man.”

And mature Campbell did. He starred in football and basketball, earning All-State and All-Western New York honors. As a senior, he was named the New York State Player of the Year in football. He graduated with an 85 average. He signed with the University of Maryland, and was expected to compete for the starting quarterback position as a freshman. He became Malik Campbell, The Greatest Athlete The City of Buffalo Has Ever Produced.

He, like so few of his East Side Ferry-Wolhers forebearers, got out.

And then, suddenly, he didn’t.

•••

The NCAA Clearinghouse ruled Campbell academically ineligible. Turner Carroll, a Catholic high school, required one religion class in each academic year. At the time, the NCAA only accepted one year of religion.

Campbell, despite taking the SATs, despite earning a scholarship, despite walking across the stage at graduation and holding his physical diploma from Turner Carroll, had to go back. And not just for one class, either. He had to go through the full schedule, just for half a credit, and he had to pass every class.

Campbell played for Ansari at Turner Carroll High School and remained close with his former coach after graduation. The pair has since reunited at Buffalo State.

“I had to realize what I was going to do,” Campbell says. “Whether I was going to give up and quit and say they didn’t allow me in, or I’m going to keep working.”

Had Campbell thrown in the towel, had he lost focus and stopped going to classes, had he slowly drifted away, no one would have blamed him. Just look at where he grew up. Anyone who gets out almost certainly gets dragged back. Look at Ritchie Campbell, and look at the thousands of other talented athletes who never even made it as far as that.

“It was tough, it was crushing,” Ansari says. “But it wasn’t like, to me, (his) life was over. Some kids get a setback like that and get down, depressed, throw their hands up, might not take that last year of school seriously and just drift off, thinking the world has done them wrong. But Malik just took it like a man. I never doubted that he was going to end up with a scholarship—it was just a question of where.”

Ansari was involved with Campbell and his family all the way through, and Campbell stayed focused, stayed out of trouble, and passed all of his classes to earn his degree. Again.

“It was tough,” Campbell says. “Every day, I got up and cussed, I fought, yelled and cussed everybody out about it. But I did it, you know?”

Campbell sat out football season while he was finishing up at Turner Carroll, but he was still playing AAU basketball. Louis Orr, then an assistant coach for Syracuse basketball, discovered Campbell while recruiting one of his AAU teammates. Orange head football coach Paul Pasqualoni had already offered Campbell a scholarship before he signed with Maryland.

Syracuse was always Campbell’s favorite school. As a kid, he was a big fan of Syracuse basketball legends Billy Owens and Derrick Coleman. But at Syracuse, a redshirt freshman quarterback named Donovan McNabb had just been named Big East Rookie of the Year, so Campbell initially chose Maryland since the Terps were offering immediate playing time.

Now Campbell had a second chance, and he chose to play basketball at Syracuse. In 1997, Campbell’s first season, Syracuse, coached by Jim Boeheim, finished first in the Big East and made it to the Sweet Sixteen in the NCAA tournament. But Campbell only saw action in 15 games. The next season, Campbell only played in 16 games, and Syracuse lost in the first round of the NCAA tournament.

According to Campbell, he and Boeheim didn’t always see eye-to-eye when it came to how much Campbell should be playing. So, Campbell left the basketball team after two seasons and switched to football at Syracuse.

“(Boeheim’s a) great guy,” Campbell says. “As a basketball coach, he has his way and he has his players. But he’s an unbelievable guy. I didn’t realize it until I left. When I started playing football, I’d go up to the office, talk to him every day, have random conversations. He’s a great guy.

“But when he’s in his basketball mode, that’s just what he’s doing, and if you don’t fit into what he’s doing, then, like any coach, they just do what they do — not to say that you aren’t a good player. I didn’t fit into his style. But I can’t be mad at that. It was what it was.”

Campbell left basketball behind and spent the beginning of his college football career holding a clipboard on the sideline as a backup quarterback. After three years away from the game, it would take a while to shake off the rust — and a little longer to learn the playbook. But Campbell was done waiting. He’d waited long enough already. He wanted to play.

“What can I play right away?” he asked Coach Pasqualoni, who told him he could try out at wide receiver and see what happens. He tried out and played immediately.

Campbell won two bowl games with the Orange, but he was never quite able to turn his immense athletic ability into consistent on-field production. In three seasons as a wide receiver, Campbell caught 59 passes for 811 yards and one touchdown. He was not selected in either the NBA or the NFL draft, and graduated with a degree in social work. After Syracuse, he played a bit in the Canadian Football League and the Arena Football League, but neither stint led to a pro contract.

“It’s not always about talent,” Campbell says. “It’s about opportunity, it’s about timing, it’s about myself, it’s about all those things that have nothing to do with talent. Had I been in a different era, I probably would be a pro. If somebody takes what I could do back then right now, I’d be a pro, no question. Kids don’t work as hard now as when I worked.

“There was a lot of great talent at (the time I was coming up). It just wasn’t the time for me. Do I think I could’ve played? Of course. There’s no question in my mind that if given the opportunity, I could’ve played. But it didn’t happen, and I’m not mad.”

The NCAA rule that declared Campbell ineligible and kept him from going to Maryland?

It no longer exists.

•••

Malik Campbell was The Greatest Athlete the City of Buffalo Has Ever Produced. But what is he now?

After his playing career ended, Campbell started coaching AAU and working as the director of a summer basketball league at the Kensington-Bailey Community Center on the East Side. He remained close with Ansari.

“We stayed family throughout,” Ansari says. “He has a daughter who is a star freshman at Performing Arts (High School) and a son who plays little league football, and we go to their games. We stick together.”

Ansari stuck with Campbell through it all — he was there to smooth out Campbell’s rough edges and he was there to help him gain eligibility. Now, after Campbell joined Ansari’s staff at Buffalo State a few years ago, they are here for each other.

“Malik just wanted to give back, basically,” Ansari says. “(He’s) not coaching for the money, that’s for sure. He’s pretty much volunteering. I think in some way, he appreciates the help we gave him coming up and he just wants to give back.

“Everything that a current player is trying to achieve, he’s already accomplished, including graduating. He’s strong and challenging—that’s the kind of player he is, and he does the same with the players, so that’s very helpful.”

Campbell seems to have found his place helping others. He pitches in with little league football, and if someone asks him to help out a neighborhood kid with some talent, he always does.

“I do it because someone did it for me,” Campbell says. “They did it for me for free and helped me get where I got to, so I feel like I have to give back. A ton of guys opened the gym up for me and let me go in and work and train and showed me different things. It was a community effort that helped me get opportunities to play.”

Which brings us back to 1995, back to the first line of that story in The Buffalo News:

“Is Malik Campbell bound for the NFL or the NBA?”

The answer, we now know, is neither.

“My day is over,” Campbell says. “You bring up a story from 1995… anything that people can say about me, you can find it. It’s over.”

And maybe it is over for Malik Campbell, The Greatest Athlete The City of Buffalo Has Ever Produced. But for Malik Campbell, Coach and for Malik Campbell, Community Leader and for Malik Campbell, Father — well, for all of those Malik Campbells, their day is just beginning.

“Is Malik Campbell bound for the NFL or the NBA?”

It was the wrong question all along.

Malik Campbell, the greatest athlete the City of Buffalo has ever produced, was never bound to be a professional athlete.

He was always bound for something more.

Charise H • Mar 3, 2016 at 1:53 am

One of the GREATEST. ….Awesome

Ray Braxton Sr. • Mar 1, 2016 at 5:01 pm

Hi my name is Ray Braxton Sr. Was a RB at Lackawanna High School from 1985-1988, was a first team Balley’s and Parade All- American my senior year. I followed Malik Campbell through high school and college, seeing him on the field and court in high school I defenitly knew he was going to make it pro in one or the other sport, I use to say to myself this kid is good and when he went to syracuse to play both sports I was like wow. See when I was in high school everybody just knew I was going to a major college and on to the pros, of course that was my dream as a kid but not knowing your dreams can end up differently, so u either except your dreams did not come true and move on and try to live a normal life or you can just throw in the towel and be a nobody. I’m glad to see Malik moved on and is giving back from his heart, I met him a few times and I always said to myself this kid is special and glad to see him working with a great man,coach Ansari. Good Luck to both men.

Mike Towns • Mar 1, 2016 at 2:54 pm

Yes Malik was a Great Athlete and humble with it !!! God Bless You Malik !!!