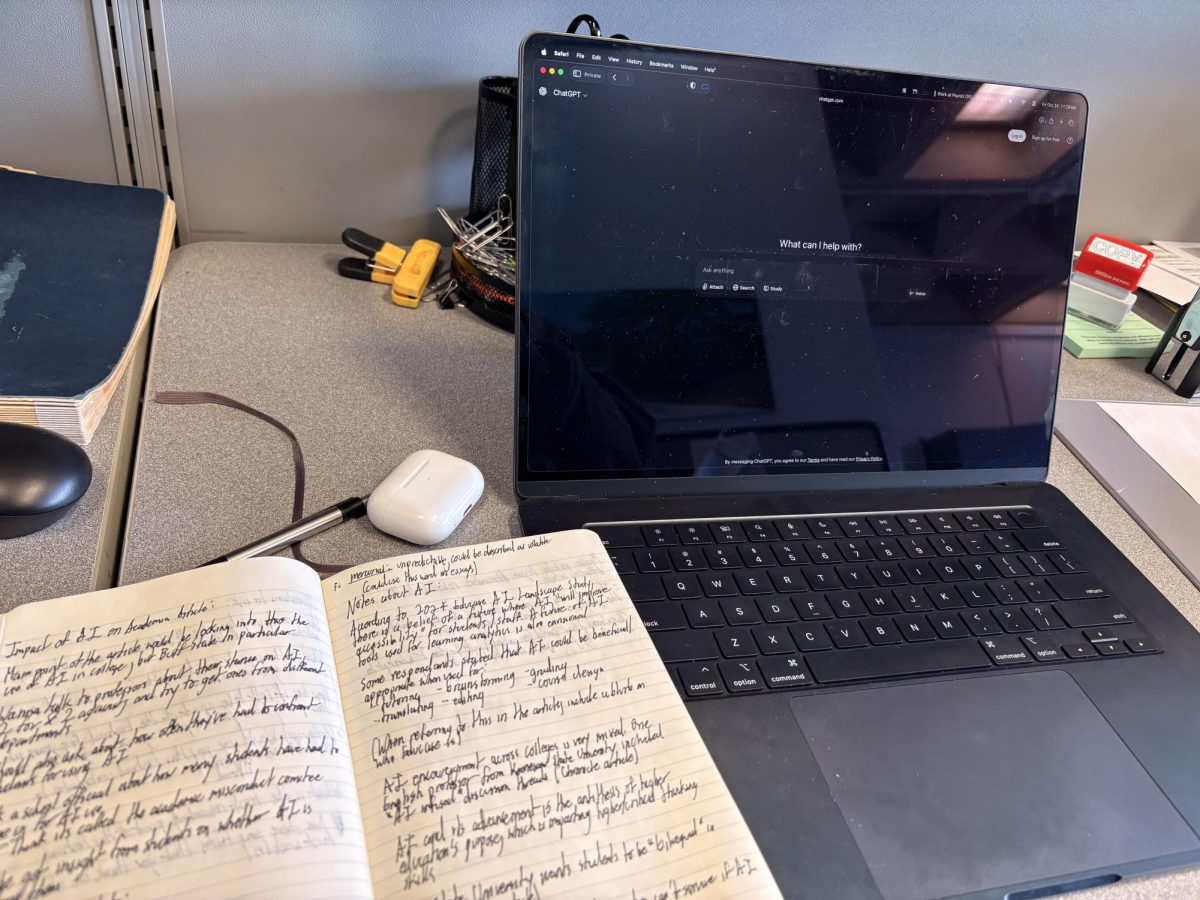

Ever since OpenAI’s ChatGPT introduced the wider public to generative AI in late 2022, students all over the world have relied on its services for their workloads.

According to an AI in Education Trends Report by Copyleaks, an organization that aims to ensure reasonable AI adoption and prevent plagiarism, over 90% of students admitted to using AI in academic spaces, with 73% stating that their use of AI has increased in comparison to last year.

The report breaks down how students utilize AI, with it mostly being used in the preliminary stages of academic writing. 57% claim to use it for brainstorming ideas, 50% for drafting outlines and 44% for generating initial drafts.

The response to AI’s growing prevalence has been mixed regarding higher education. Jeanne Law, an English professor at Kennesaw State University, spoke with “The Chronicle of Higher Education” about how she integrated AI into her classroom with “AI-infused discussion threads” where students are taught how to insert prompts into an AI chat bot so that it help them comprehend the elements of rhetoric, including audience, purpose, context and genre.

Ohio State University takes it one step further, aiming to integrate AI learning campus wide. In June 2025, the university announced an “AI Fluency Initiative” to embed AI education into every undergraduate curriculum beginning the next Fall semester.

While some universities across the country are outspoken on AI’s presence on their campus, Buffalo State University has not addressed whether it is welcomed or rejected in its curriculums.

The university’s Academic Misconduct policy has not been updated since June 2021, meaning AI has no mention in the university’s approach to what can be determined student misconduct.

Within individual classrooms at Buffalo State, AI acceptance varies from professor to professor. Four professors were able to provide their own comments on AI’s place in higher learning, two in support of its use and two against.

Dr. Aimable Twagilimana, an English professor, views AI as a tool that should be understood.

“I want students and instructors to think of AI as a tool,” he said. “This is an additional research tool where answers can come faster. I hope that students do themselves a favor and don’t use it to find quick and easy answers. Instructors think AI will replace them, but I don’t believe that, especially when it comes to teaching literature. Literature is something pure, something where a class of 23 people will read something and you get 23 different answers.”

Dr. Twagilimana also touched on a growing inequality between schools based on their AI adoption. He drew comparisons to when the internet first came into prevalence.

“In the 80s and 90s, Buffalo public schools in the inner city didn’t have any viable internet, so they fell behind,” he said.

In contrast, Dr. Macy Todd, also an English professor, denounced AI’s use, stating that it should not be involved in the academic space.

“Students don’t want professors using AI at all,” he said. “Regardless of what students themselves do with AI, they do not want courses designed by AI or it being used to grade their work. I’ve found it quite useless for those tasks anyway. Like anyone curious, I played around with it and found that it was pretty bad at doing those things.”

Dr. Todd built on this by claiming that student work written by AI is of lesser quality as well. He spoke of how he used to have students write responses to develop skills such as producing arguments based off complicated, contradictory data, and that when AI makes responses based off these parameters, it is lackluster in comparison.

“It’s a drag for me to read that writing,” he said. “Students can really sit down and engage with the material, and the writing that they produce, even if it’s not ‘clean,’ is still quite interesting to me.”

Dr. Laurie Buonanno, a political science professor, encourages her students to use AI to aid them in the classroom.

“I allow my students to use AI, but I do warn them that if you’re going to write an essay with it, you have to cite it,” she said. “They have to cite that they used it and which AI platform they use, because even though it’s a machine it’d still be plagiarism.”

Dr. Buonanno also touched on how AI can be a great accessibility tool, where non-native English speakers can use it to help craft things such as memos.

“Why would I prevent non-native English speakers from using AI when they are competing with native English speakers?” she said.

Dr. Eric “Luke” Krieg, a sociology professor, believes that once students rely on AI to do their work, it removes the entire purpose of learning in the first place.

“My goal in teaching is not for students to necessarily go out and get the right answer,” he said. “AI makes it very possible for students to go and get the ‘right answer.’ If you think of education as the student just trying to find the right answers for everything, then AI serves that purpose, but does that really enable a student or anyone else to think more clearly about the world?”

Dr. Krieg goes on to state that no technology is inherently good or bad; it is dependent on how it is used. He also listed some positive use cases for AI, such as using it to parse through thousands of emails. He gave a specific example in the context of performing research.

“In things like research, they are finding great uses,” he said. “You could have 100 dolphins talking to one another, and AI can detect which dolphin is responding to what, and now you can start to answer questions like ‘do dolphins have language?’”

He went on to reinforce that it has no place in the classroom, however.

“If a student comes away able to ask their own questions about why we have environmental problems and how they might come at that through different theoretical perspectives, that’s great,” he said. “But I don’t want a student using AI in my class to demonstrate that they understand the difference between an eco-Marxist perspective and an eco-feminist perspective. I don’t see the gain in that.”

Whether embraced or rejected, AI is no longer an abstract concept but a real presence in classrooms and research alike. As Buffalo State navigates its place in this new digital landscape, the challenge will be finding a balance between maintaining academic standards and adapting to the tools that are reshaping how students think, write, and learn.