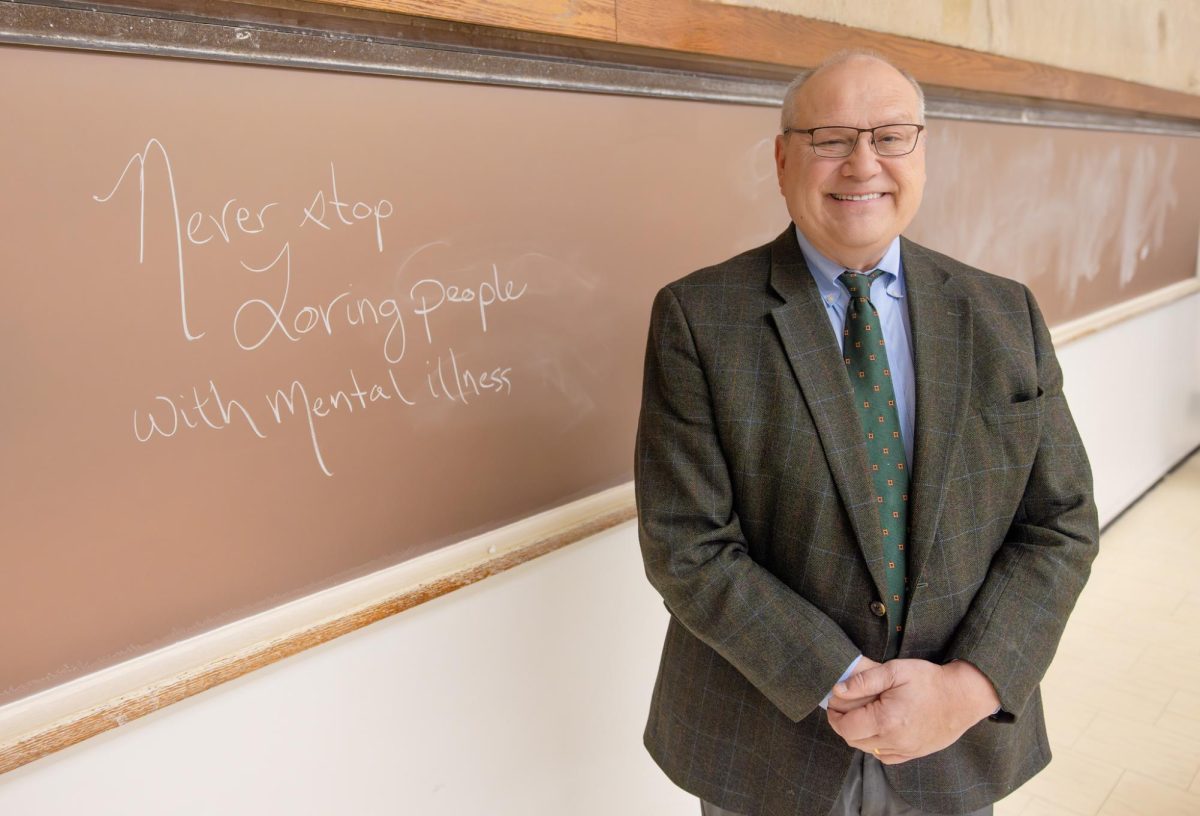

Dan Lukasik, New York State Judicial Wellness Coordinator and Buffalo State alumni, came to campus Feb 25 to screen his documentary, My Brother Lost in Time: A Bipolar Life. It is a short film exploring the relationship between himself and his late brother, Paul Lukasik, who struggled with Bipolar disorder.

A 1988 graduate of the University at Buffalo School of law, Lukasik has built himself up to be a major figure over the course of this career. After serving as a trial lawyer for over 30 years, Lukasik now serves as Judicial Wellness Coordinator for the New York State of Court Administration, providing resources and support for judges with mental health struggles. He is also currently a professor at the University at Buffalo School of Law, teaching the importance of mental health and well-being in the legal profession.

Following a depression diagnosis at age 40, Lukasik has made major strides in breaking down the stigma around depression and other mental illnesses, launching his website Lawyers With Depression in 2005. His work regarding mental health has been widely recognized, being featured in notable publications such as The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The National Law Journal, and NPR. He is a recipient of the Public Service Merit Award from the New York State Bar Association.

Recently, in collaboration with the Patrick P. Lee Foundation, Crisis Services, and the Suicide Prevention Coalition of Erie County, Lukasik produced a short documentary that details the life of he and his brother’s struggle in dealing with mental illness. It is currently available for free on YouTube.

Lukasik screened this documentary in the Bulger Communication Center, with Buffalo State students filling the audience and watching the film closely.

Following the screening, he began speaking to the audience, describing what inspired him to make this film.

He told a story of how he was seated in a coffee shop about one year ago, struggling to put together an article for the Buffalo News about his relationship with his brother and the importance of understanding mental health. He was approached by a local photographer he worked with before, who saw his struggle in finding the right words and gave him a recommendation.

“He put his hand on my shoulder,” Lukasik said, “and he said, ‘You should meet my son. He’s an independent filmmaker.’ So a week later, I met up with his son in a Starbucks, and I told him the story about my brother and I.”

Lukasik continued, “I said to him, ‘To be honest with you, thanks for listening to my story, but I know documentaries cost a lot of money.’ But he says to me, ‘Listen, I’m a storyteller, and I’m gonna tell this story.”

Lukasik goes on to detail the journey he had in creating this documentary. He explains how it took two months to film, and once fully completed, they struggled to find out what the next move was.

“We didn’t know what to do with it, so we brought it to Crisis Services of Erie County. We showed them the film, and that was the beginning of it making its way to all these screens, and having so many other people involved.”

One notable contributor was Patrick Lee of the Patrick Lee Foundation. An entrepreneur who lost his son to mental illness, upon seeing the film, he immediately wished to get behind it. He proceeded to bring the film to the spotlight, hiring communications directors, marketers, and contacting PBS Television, culminating in a premier at the University of Buffalo with a theater filled to the brim.

Now, the film is being screened all across the country.

Lukasik ended his talk reflecting on the paths that he’s taken over the course of his life, and how important it is to speak about mental illness.

“So here I am, almost 50 years later. I took my first psychology class in this building. Now, I’m just thinking back about all the things that have happened to me. All the wonderful things, all the tragedies, and this by far is the biggest one. It not only spoke to my own experience of mental illness, but also love, and at the end of the film, that’s the takeaway. Never stop loving someone with mental illness, and never stop hoping. So maybe it didn’t save my brother, but it could save yours, or your mother, or your friend, or your coworker. If some good can come out of that, I am determined to make that happen. So, thank you.”