160 Years, Part I: Black History and the interpretation of…

“Slavery and its Fruits,” an article published in The New York Times (Aug. 26, 1859)

February 7, 2019

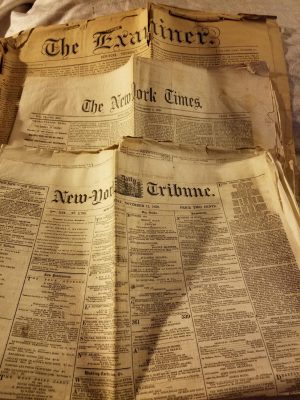

This past December, a friend gifted me a collection of newspapers, including The New York Times, The Examiner and New-York Daily Tribune, that were published between 1859 and 1862.

While there were many things that I found beyond interesting, like $3 shoes and a letter from a reader about “Toads Undressing Themselves” in his yard (seriously?), most astonishing to me was being able to look at Black/African-American culture, or the portrayal of it, anyway, 160 years ago.

Knowing these papers were published just two years before Abraham Lincoln’s presidency and the start of the American Civil War, and four years before the Emancipation Proclamation, I was prepared for the types of issues and language I would find in reference to African Americans, most of who were still long ways from freedom.

Though the countless articles about slavery, as well as the many references to those of African descent as “negroes,” “the blacks” and even “savage[s] in the depths of the Dark Continent” were painful to read, I found it a privilege to hold in my hands the history of my heritage from nearly two centuries ago.

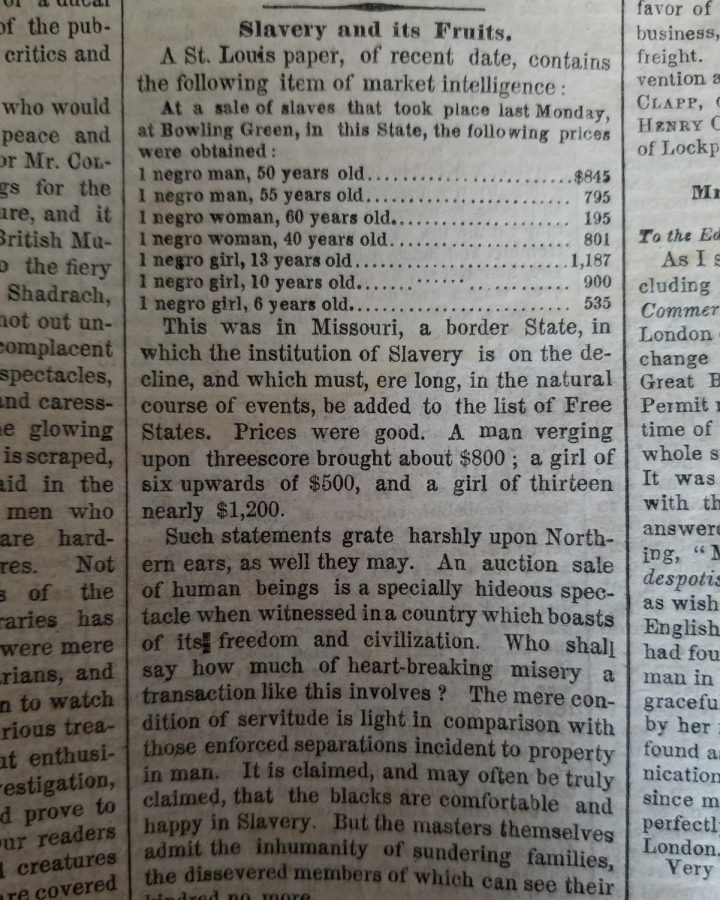

Although most discourse about slavery in these articles unsurprisingly referenced the South, one of the most striking pieces by way of The New York Times (Aug. 26, 1859) showed that the Midwest still lacked the progressive spirit of the North during this time.

The article, titled “Slavery and its Fruits (pictured atop the page),” referenced an “item of market intelligence” from a paper published in St. Louis that listed the genders, ages and prices for slaves in Bowling Green. Prices for “negro” men, women and girls ranged from $195 to $1,187.

Though the tone of this Times article is largely condemning of slavery, with the writer (unnamed, as many newspapers were not yet using bylines)  describing the very concept as “a specially hideous spectacle,” it also references, and the writer seems to sympathize with, claims that “the blacks are comfortable and happy in Slavery.”

describing the very concept as “a specially hideous spectacle,” it also references, and the writer seems to sympathize with, claims that “the blacks are comfortable and happy in Slavery.”

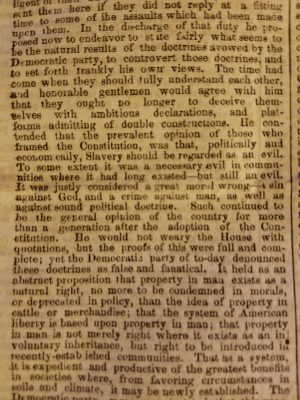

I found this conflict in other stories as well, where slavery would be described as “evil,” but a “necessary evil,” as was argued among the House of Representatives in the First Session of Thirty-Sixth Congress (via New-York Daily Tribune, Feb. 11, 1860 edition). Even in the progressive North, the climate was certainly lukewarm, and this was made apparent through the news articles that were published during the time.

Conflict was certainly apparent in the government, as well. The political scope in 1859 was drastically different, with the Democratic party holding more conservative, traditional views (especially regarding slavery) and the Republican party subscribing to a more liberal philosophy, sympathizing with the plight of African-Americans.

Today, majority of African-Americans vote Democrat, even if they don’t formally subscribe to the political party. It is interesting, to say the least, that the same party that fought in Congress to establish that slavery was a “God-given right” and that the liberties granted in the U.S. Constitution applied only to the white race now thrives on the black vote.

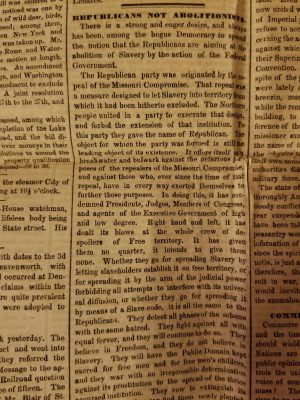

Just as interesting to me is the relationship between Black America and the Republican party, which, according to a Times article from Dec. 10, 1859 (Drift of the Republican Party), was birthed as a “resistance…to the extension of Slavery into the free territory of the United States.”

Even still, some would make a point to clarify that not all Republicans were fighting the cause to end slavery. In the aforementioned edition of New-York Daily Tribune which contained the Congress session, a writer targets “the bogus Democracy” in the article “Republicans Not Abolitionists.” He goes on to express in the mudslinging article that “the Republican party is not an Abolition party” and that it did “not wish to interfere with Slavery in the States where it exists.” As often appeared the case throughout much of American history, African-Americans were treated as a byproduct of a bipartisan feud as opposed to human beings deserving of rights and American liberties.

Even still, some would make a point to clarify that not all Republicans were fighting the cause to end slavery. In the aforementioned edition of New-York Daily Tribune which contained the Congress session, a writer targets “the bogus Democracy” in the article “Republicans Not Abolitionists.” He goes on to express in the mudslinging article that “the Republican party is not an Abolition party” and that it did “not wish to interfere with Slavery in the States where it exists.” As often appeared the case throughout much of American history, African-Americans were treated as a byproduct of a bipartisan feud as opposed to human beings deserving of rights and American liberties.

As a journalist, I have been told in many ways by many people that an important role of the reporter is to serve as a voice for the voiceless; to defend those who cannot defend themselves. In times when the African-American community had no voice, the ‘voices’ that were sought to represent us in politics and news media misrepresented, disrespected and failed us completely.

It is astounding to marvel at the evolution of American journalism and politics, especially in relation to the African-American community. Minorities are still greatly misrepresented in both of these areas, which is why many of the social issues of today persist. History has established a population trying to remedy a place into a socio-political system where its members were akin to the papers on which words about them were printed; pieces of property deserving of neither respect nor regard.

I will just as readily admit, however, that the progress which has been made is undeniable. The greatest difference between modern times and nearly two centuries ago is the voices speaking for our communities and population are now from our communities and population.

Looking to the past reminds me of how my forefathers and mothers earned the right for my freedom of speech and mind, both as an African-American and as a journalist. I share these stories because I hope the same for others, that we use history not as a stone to throw, but as a stepping stone to rise further above the strongholds of past and present injustices, especially within our political system and news media.

This is Part 1 of a 4-part series; tune in next Thursday as I use an issue of The Examiner to analyze a pillar, both past and present, of the African-American community: Religion.

eberhaij01@mail.buffalostate.edu

Betterposture • Feb 10, 2019 at 2:52 pm

Thanks so much for the post.Really thank you! Keep writing.

Yazz Eberhardt • Feb 8, 2019 at 11:13 pm

Great article Jaji!