More people pass U.S. citizenship tests today than previous years. That doesn’t mean the test is easier.

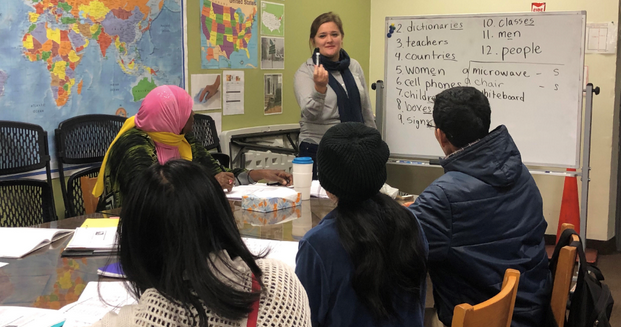

Students learn English during ESL class at Jericho Road.

January 29, 2019

Inside Jericho Road Community Health Center on a recent Tuesday afternoon, a few clear voices ring through the off-white-colored rooms.

“What do you drink?” asks instructor Christina Longanecker, enunciating every syllable.

“I drink tea,” a diversely aged group of students sitting around a small, rectangular table answer in unison.

As Longanecker goes through several rounds of questions and answers, some easier than others, students pay rapt attention, smiling and laughing with each other. Nobody at this table appears to be taking education for granted.

Some of these students, coming from countries such as Yemen, Burma and Somalia, are learning English to assimilate better in Buffalo.

Others are taking ESL classes in order to pass the Naturalization Test, which includes a comprehensive application, interview and civics and English tests.

Those students face a much more difficult test in 2019 than previous generations did.

Antony John Kunnan of California State University studied the history and effectiveness of the Naturalization Test in his article “Testing for Citizenship: The U.S. Naturalization Test.”

Kunnan found that in the 1990s and through the early 2000s, the test was less intensive, but not necessarily better. He wrote that the applicant needed to hold a basic conversation with the interviewer, which they still need to do today, read one sentence, write one sentence and correctly answer at least six civics questions, out of a list of 100.

Problems with the old tests included a lack of uniformity, unclear passing guidelines and the encouragement of memorizing facts instead of understanding American history, Kunnan wrote.

The government started redesigning the test in 2002, enlisting ESL experts to redesign a test that “should be more meaningful and not promote memorization of facts and sentences like the current test; and the redesigned test must be more fair to applicants,” Kunnan found.

In the 2003 pilot test, 10% of test-takers “performed poorly,” though they passed the previous test, Kunnan wrote.

Kunnan found that the redesigned test, implemented in October 2008, proposed some of the same problems and new ones. The goal of moving away from reading and regurgitating facts and emphasizing critical thinking responses “regarding U.S. history and government would be beyond the level of English expected in the test” wasn’t achieved because English is a second language for most applicants.

Khadaj Ruafai knows this well. Ruafai is taking ESL classes at Jericho Road, but she doesn’t carry the stress of a looming citizenship test. She came to the United States from Somalia 20 years ago and passed her citizenship test 15 years ago. In it, she said she answered only three or four questions, which she described as very easy. She said she pretty much only learned her name and address.

“I was lucky,” Ruafai said.

An American citizenship test includes reading, writing, speaking and civics. Applicants study a list of 100 civics questions, of which they’ll be asked 10 random ones that include: “How many amendments does the Constitution have?” and “The House of Representatives has how many voting members?”

A lot of Americans couldn’t answer those questions.

A survey by Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation released in October found that out of 1,000 Americans who took a mock citizenship test, only 36% passed.

“It’s really a stressful process. Especially, like, they don’t entirely understand the political things that are happening right now but they know things aren’t great and they understand enough to be nervous,” Longanecker said.

However, more people are passing tests today than before. David North, a Fellow of the Center for Immigration Studies, found that 34% of applications were denied, compared to 8% today. He believes there are three reasons for this: a change in applicants’ education levels, more test preparation and lower test standards. Applicants cannot be asked anything that isn’t on the study guides available online.

North calls today’s process “more relaxed” than the one in the past.

“Once they finally pass, it’s just like a weight off their shoulders. You can almost see them like just physically chill out in class,” Longanecker said.

After studying at Jericho Road for the past two years, Afrah Fadel she passed her citizenship on Oct. 20. It was her third try. To say the least, she’s happy.

“Very, happy. Very, very happy,” Fadel said with a laugh.

She followed her husband, who passed the test in September, to America on Sept. 17, 2014, from war-torn Yemen. Even after passing the test, she’s not done learning English, but now it’s for her own ambition at her own pace.