Opinion: Being plugged into social media is fun, right?

Man, what a paradox we are.

Yes, I have a photo I took of avocado toast, a latte and my laptop readily available.

March 12, 2018

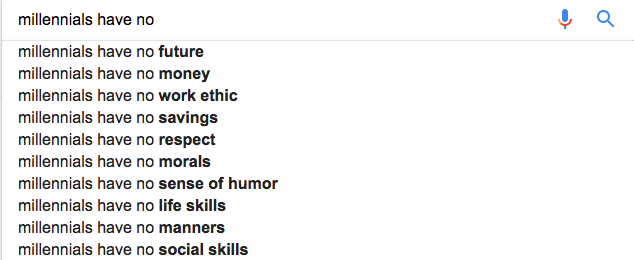

Millenials have been reduced to avocado-toast eaters, Walmart-killers (although I’m still racking my brain on how this is a bad thing..,) texting, smartphone-obsessed robots, people who, gasp, wear rips in their jeans. Aren’t your knees cold?

But it’s not just that. Avocado toast represents something else. When people complain about millennials eating avocado toast, it’s not because we’re eating fiber-filled whole grain bread with avocados high in healthy unsaturated fat, which are proven to reduce heart disease.

It’s because millennials spend our money on useless things, need everything to be different and better, (RIP Buffalo Wild Wings, you weren’t very Buffalo or wild…) what was wrong with peanut butter toast? Because millennials have no money saved or are we actually rolling in dough? Because millennials need to post their whole lives on social media, starting with their highly Instagrammable avocado toast.

You know when the decades become looked at as decades? Instead of “a couple years ago” we say “in the 80’s,” it seems we’ve gotten to this point with the internet.

The rise of the internet has been a 20-year-long whirlwind– from Google providing access to information all over the world at your fingertips, to Yahoo Answers paving the way for anonymous online advice, giving and receiving, to Youtube, then Myspace, then Facebook, then Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat converting our social and professional lives from “in real life” to virtual. To have a need for the term “in real life” in daily conversation– decades ago, would anyone have guessed we would have to distinguish between “real life,” that life itself could be something other than real? The internet doesn’t even need to be capitalized in AP style anymore as if the grammar decision-makers sighed and said: “well I guess it’s here to stay.”

And now that it’s been a few years, we’re thinking about it in terms of trends, changes and all we have done right and wrong. Before reading the rest of what I have to say, I would suggest reading the two pieces I’ve bolded in this article, written by much more talented writers than I, putting these thoughts into writing better than I ever could, supported by personal testimony and fascinating, revealing studies.

Where millennials come from

New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino navigates different arguments in this piece made by several authors about millennials, most of them quite negative. The takeaway? Every generation has had their fair share of judgments, and millennials are no different, but millennials are quite ambitious and self-serving, with the art of studying and creating oneself, which is an expected product of their environment.

And does that not make sense?

As a young millennial, borderline Generation X depending on who you ask, I have never lived in a world without the internet. In elementary school, much of my life revolved around online/simulation games geared toward children only, where I could buy a “real life” toy, like a Build-a-Bear or a Webkinz stuffed animal, and then play as an avatar online.

In my own little online world, I could buy my own things, have my own house decorated my own way and meet up with friends. Those were all things that a child living in rural Western New York couldn’t do. Anywhere I went, I was driven there and accompanied by my parents. I was a kid, but living in my online fantasy world, I felt like a grown-up in control.

The internet was a beloved thing to me, perhaps more than most children I knew. I started a blog about an online simulation game I loved, Build-A-Bearville, at ten years old. At age eleven, I decided I was first of all, too old for Build-A-Bear, and second of all sick of it so I bluntly wrote:

“I’m sorry everyone but I’m taking a break from WordPress and this blog. It is like a chore for me now, I don’t enjoy it at all…Updating about everything that happens in BABV is too hard to keep up with when u r only on once a week or once every two weeks. I just cant keep it up and updated anymore, especially with my busy summer schedule. Maybe sometime I’ll start it back up again, but for now I’m just far too busy… I’ll keep it up for a little while so u can still talk, but I probably wont b on it often and won’t be updating it.”

My parting post reads like a harsh breakup text, and in a way it was.

I was pouring my heart and soul out on the internet. I lived an alternate life on it, finding solace in the fact that my readers didn’t actually know me in person, and never would. This was at a time when people still went under pseudonyms, otherwise known as usernames, and didn’t share personal information deemed too personal online.

As I grew up, the internet grew even more intertwined with me. I scoured it, reading the blogs of women and young girls across the world, reading fashion magazine articles (including many, cringe-worthy “pre-woke” ones, instilling sexist ideals on young me and many others my age,) and checking Facebook obsessively.

I watched social life change from “real-life” in school to online. I witnessed the birth and death of Snapchat best friends (was so-and-so cheating on so-and-so? They’ve been number one Snapchat best friends for a month,) the rise of “liking” someone’s filtered photo to flirt with them (yay! “blank” liked my selfie!) the start of awkward meet-ups with people you feel you know really well on social media only for them to be completely different than you expected them to be in person.

Social media trends, apps and social rituals were birthed in front of my eyes at a very primitive age, when I was shaping, shifting and changing my worldviews by the minute, all while juggling this new world nobody understood or knew the repercussions of– or at least talked about.

Being raised in a world where you get to craft yourself online with editing, filters, backspace keys and auto-correct, makes it easy to understand why millennials are the way we are. Surrounded by content, surrounded being nearly an understatement, and the ability to peek into anyone’s social and professional life on Twitter and Instagram has given us all a starving ambition, to live a life like those we see or read on the internet. These extreme aspirations, mixed with a self-importance born out of the movement that everyone is a unique, shining star who can do anything, leave millennials with a growing pressure manifesting itself in a “twitchy,” to borrow Tolentino’s word, anxiety. Tolentino writes:

“I also took six classes a semester, worked part time, and crammed my schedule with clubs and committees—in between naps on the quad and beers with friends on my porch couch and long meditative sessions figuring out what kind of a person I was going to be.

Most undergraduates don’t have such a luxurious and debt-free experience. The majority of American college students never live on campus; around a third go to community college. The type of millennial that much of the media flocks to—white, rich, thoughtlessly entitled—is largely unrepresentative of what is, in fact, a diverse and often downwardly mobile group. “

Millenials aren’t snowflakes, most people I know are working themselves to the maximum of their potential, going from class to next class, project to next project, club meeting to next club meeting. We work, we post on social media and we get involved in politics and social issues.

My favorite part of Tolentino’s piece is this paragraph:

“Over the last decade, anxiety has overtaken depression as the most common reason college students seek counseling services,” the Times Magazine noted in October. Anxiety, Harris argues, isn’t just an unfortunate by-product of an era when wages are low and job security is scarce. It’s useful: a constant state of adrenalized agitation can make it hard to stop working and encourage you to think of other aspects of your life—health, leisure, online interaction—as work. Social media provides both an immediate release for that anxiety and a replenishment of it, so that users keep coming back. Many jobs of the sort that allow millennials to make sudden leaps into financial safety—in tech, sports, music, film, “influencing,” and, occasionally, journalism—are identity-based and mercurial, with the biggest payoffs and opportunities going to those who have developed an online following.”

For a while, I have not been able to pinpoint the source of mental exhaustion. Tolentino and author Malcolm Harris pin it down– it’s not that millennials are working more hours, it’s that we look at parts of our life that are not considered work, not anything we usually get paid for, as work. For anyone who lives their life largely online and has at least somewhat of a following, even if it’s just a lot of people you know, social media is work.

More than I’d care to admit, I spend time thinking about what Instagram picture I could take, thinking of potential captions. When I go somewhere photogenic; the park, a museum, walk outside on a nice day, a trendy cafe, or I like my outfit… taking a photo for Instagram is on my mind. Nobody expects me to do it, or will pay me for it, but it’s a job I’ve given myself and prioritize.

It’s not just trivial Instagram photos, and I genuinely do enjoy Instagram photos. It’s not like the whole time I’m crying “why must society make me take Instagram photos!!?” like a Saturday Night Live character.

The struggle with this addiction to the internet is that it’s not something I, and many, want to give up. Because it’s something that is given up so easily. Just delete the app. Delete your account. Many people I know work in social media, and they’re great at it. Witty tweets and staged flat-lays are their strong suits.

“A constant state of adrenalized agitation can make it hard to stop working and encourage you to think of other aspects of your life—health, leisure, online interaction—as work.” (Tolentino) When your part-time job is the last thing on your list of priorities, your life can feel like a laundry list of never-ending expectations. Anxiety runs rampant among college students because our lives are decentralized. We’re constantly running from thing to thing, usually only getting paid to do one, or even none, of those things, not necessarily needing to do any of it. Our mindsets have changed, we don’t see the difference between meetings, classes, work, internships, socializing, homework, writing, creative projects and updating our social media. These are all daily expectations where the line between work and pleasure is increasingly blurred.

There is another emotion that Tolentino doesn’t touch on– guilt. Wrestling around in my head all day like a snake, strangling my other thoughts, is ambition. Ambition to be as intellectual as possible (you don’t read enough,) to have the best resume as possible (you’ll never get hired if you don’t do this,) to be perfect. The perfect friend, daughter, girlfriend, writer, student. Being guilty that you’re not perfect and guilty that you even care. When the pressure is on to be all of these things, and the path to being all of these things takes frequent dedication, all facets of life start to feel like work. And that can’t be far from the definition of self-obsessed, but where do we draw the line between necessary ambition to achieve what you want and obsessing over yourself? Is ambition, and the desire to be great, not self-obsessed at its heart? And, as Tolentino says, creating an online persona is imperative for many jobs, especially in media. Lauren Duca, a political columnist from Teen Vogue, got her job because the editor of Teen Vogue thought she was funny on Twitter.

For Two Months I Got My News From Print Newspapers. Here’s What I Learned.

The headline of this New York Times article by tech columnist Farhad Manjoo speaks for itself. For Manjoo, an avid consumer of news and subscriber to alerts on his phone, switching to consuming content in print every morning instead of digitally during all hours of the day was freeing. He refers to it as “slow-jamming” the news.

“It has been life changing. Turning off the buzzing breaking-news machine I carry in my pocket was like unshackling myself from a monster who had me on speed dial, always ready to break into my day with half-baked bulletins.”

He sums up the piece with three things he learned; get news, not too quickly, avoid social.

As a student journalist, obviously, I care about the news. I am a news junkie and push notifications are my fix. But it’s not just journalism majors who feel pressure to consume the news obsessively. Our current political climate and all its newsworthy, buzzing, downright shocking twists and turns are leading many to turn to the internet like its a reality show and we’re all the players. We hear it over and over again: I’m exhausted from the news.

In a world where you’re constantly plugged in, even unplugging comes with stress. Because even if you turn your phone off, you’re only leaving more work for future you. More emails, tweets and headlines to read later. And it doesn’t help that CNN uses the term “Breaking News” too liberally, making your heart skip a beat multiple times a day, but it’s just play-by-play alerts about Donald Trump and Stormy Daniels’s affair, which I guess we needed.

More than ever before, given the combination of social media addiction, news accessibility and shocking headlines that you assume are clickbait but is actually real news, people are reading the news. People all over are feeling the need to be online personalities, and that means being well-informed in current events and popular memes. See something interesting, write a 140-character witty commentary. It’s fun. But it feels a lot like work.

Is avocado toast old yet?

Twitter: @chessabond

Email: [email protected]

(For the record, this is written by someone who posts on Instagram several times a week, consumes news like it’s water, and has dropped one too many dollars on avocado toast).