Buff State grad student reflects on her time abroad in Rwanda, land of a thousand hills

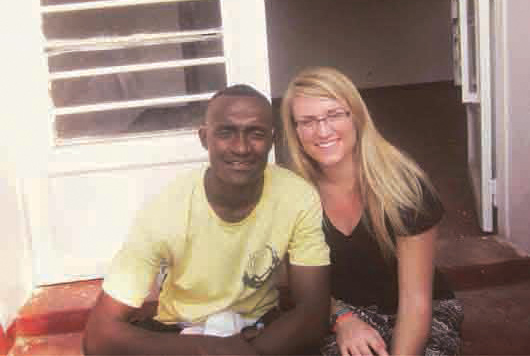

Ashley Weselak and Pacifique Niyonsenga

December 2, 2015

The “Visit Rwanda” webpage of the Rwandan government website reads as follows:

“Rwanda is a green undulating landscape of hills, gardens and tea plantations. It offers tourists a one of a kind journey – home to one-third of the world remaining Mountain Gorillas, one-third of Africa’s bird’s species, several species of primates, volcanoes, game reserve, resorts and islands on the expansive Lake Kivu, graceful dancers, artistic crafts and friendly people.”

The blog, “Buffalo2Rwanda,” maintained by SUNY Buffalo State graduate student Ashley Weselak, supports that claim. In the photos she shares, Rwandan children and adults alike can be seen surrounded by lush green vegetation, and smiling as they work, play and take up dancing lessons.

In January 2015, Weselak, an English education major, became the first non-drama major to partake in the Anne Frank Project’s (AFP) annual trip to Rwanda. The AFP teaches individuals how to use the dramatic arts as a means of community engagement, conflict resolution and identity exploration. In Rwanda, the AFP educates teachers to use their methods in the classroom environment.

“I was expecting it (Rwanda) to be really harsh. I thought there would be evidence of the genocide everywhere, and it wasn’t like that at all,” Weselak said. “It’s a really beautiful place.”

Weselak’s expectation of Rwanda’s condition is understandable. The 1994 Genocide is perhaps what the country is most known for, given that it’s recent history and the prominence of the 2004 film “Hotel Rwanda” based on the event.

The Rwandan genocide is the single greatest loss of human life since the Holocaust. Within hours of the assassination of former President Juvenal Habyarimana, violence erupted in the capital city of Kigali, and soon spread throughout the country.

Over the course of 100 days, an estimated 800,000 to 1,000,000 Rwandans were killed. Some were hacked to death by machetes at the hands of their neighbors. Millions of Tutsis and moderate Hutus fled to neighboring countries seeking refuge from the violence.

While the landscape may have recovered, the aftermath of the genocide still lingers. According to aggregate data presented by Survivors Fund, the genocide facilitated the rape of an estimated 250,000 to 500,000 women; 20,000 of whom later gave birth; 70 percent of rape survivors are HIV-positive; 50,000 women widowed; 75,000 children orphaned; and as of 2007, at least 40,000 survivors were still homeless.

Multiple studies presented elsewhere estimate that 20 percent of the Rwandan population meets established criteria for PTSD diagnosis.

Twenty-one years later, Rwanda is still in recovery from the past they both acknowledge, through memorials, museums, and events, but are also trying to leave behind.

It’s no easy task, but they are making progress according to Weselak:

“There didn’t seem to be tangible Hutu or Tutsi tension,” Weselak said. “Part of our trip was visiting a genocide prisoner’s camp. We were accompanied by the commissioner of the prison. There were maybe four guards for the camp of thirty prisoners. They didn’t carry guns, and there were no fences, just shrubs marked by the perimeter of the camp.

Having read about US prison culture their system was nothing like what I expected. The commissioner walked with us and as we walked she would stop to talk, laugh and even sing and dance with the prisoners. They seem to be much more focused on reintegration than punishment.”

The prisoners Weselak encountered were given merciful sentences through Gacaca trials — a Rwandan judiciary practice. These perpetrators were deemed to be truly sorry by their victims or more commonly, the victim’s family, according to Weselak, who approves of the Rwandan system.

The prison camp the AFP visited is not emblematic of the system as a whole. Human Rights Watch and multiple news organizations have filed reports on both the failure of Gacaca trials to enforce justice equally and on inhumane prison conditions at other locations.

It wasn’t just the prison where Weselak witnessed a sense of community. At the mention of Hutu or Tutsi relations, she said that Rwandans would often interject by saying, “We are all Rwandan.”

Weselak and the AFP group traveled to the Muhanga region east of Kigali to visit a large orphanage and school complex. While there she learned that the term “orphan” is considered derogatory.

“As soon as I referred to the children as orphans,” Weselak said, “the Matron, Mama Arlene (an American woman), said, ‘Don’t call them orphans, they are not orphans, these are my children.’”

It should be noted that the statement, “We are all Rwandan,” is the official stance of a government with a reputation for jailing “dissenters” and “divisionists,” and that the government intends to close all orphanages by 2020.

Rwanda is a nation of children and young adults. A 2015 Central Intelligence Agency report estimates that In Africa’s most densely populated country, 41 percent of the population is age 0 to 14, and 18 percent are age 15 to 24. Among children age 5 to 14, 35 percent (783,113) are engaged in some sort of child labor, which the CIA defines as:

“Work that deprives children of their childhood… that is harmful to physical and mental development…that is mentally, physically, socially, or morally dangerous…may deprive them of the opportunity to attend school… that involves children being enslaved, separated from their families, exposed to serious hazards and illnesses, and/or [sic] left to fend for themselves on the streets of large cities.”

For Weselak, working with the children of Rwanda subjected to those conditions had the most meaningful impact. A chance encounter with a 23-year-old man, Pacifique Niyonsenga, opened up opportunities beyond that of the scope of the AFP trip.

Pacifique, a genocide survivor, was given a rare opportunity when at the age of 12 he was informally adopted by a Canadian man, Bruno, living in Rwanda. Bruno paid for Pacifique’s education through high school and offered to pay for his college in Canada. However, Pacifique declined so that he could stay in Rwanda to help children growing up in similar circumstances.

“I met Pacifique at the hostel we were staying at,” Weselak said. “He was there to use the free Wi-Fi. And when he overheard me talking to someone about the prison camp he asked why we were there. When I told him I was an Education major visiting with the AFP, he immediately opened up and began showing me his files and pictures of all the children he works with.”

Pacifique runs the NIYO Cultural Centre, which he founded in 2012. At the center, Pacifique teaches children to perform traditional Rwandan Intore and Amaraba dances as well as to play the drums. Pacifique and the children then put on free shows around the city to gain donations that go towards supporting the children’s formal education.

Primary and secondary education is free for Rwandan citizens. However, it isn’t free for the homeless, and they must cover the cost of materials as well. The cost amounts to $100 to $150 per year per child. But in a country with 63 percent of its population living well below the international poverty line of $1.25 per day, the cost of $100 per year can be insurmountable.

Pacifique’s program is a growing success. Currently, he supports 60 children through the drum and dance shows and by selling his artwork. He will continue to take on as many children as he can support.

“I am able to do what Bruno did for me 60 times over,” Pacifique said.

Pacifique also teaches the children’s mothers to make Rwandan inspired fashion accessories that they can sell at the NIYO center in order to support their families.

Pacifique hopes to build a vocational school as a part of his non-government organization that will be able to prepare 600 children for specialized work.

As a 24-year-old student and teacher, Weselak admires Pacifique’s ambition.

“He makes me feel very lazy,” she said jokingly.

Weselak hopes to return to Rwanda on a Fulbright scholarship following the completion of her master’s degree this semester. She wants to continue to work with Pacifique and bring inquiry-based learning to the Rwandan education system. She believes that a meaningful education will improve lives and prevent violence as seen in the Rwandan Genocide and more recently in parts of the world like Syria.

“I hope that more student teachers will partake in these trips in the future,” Weselak said. “I see these kids suffering and I think of all the ways education can help. Pacifique has become a mentor to these children, and I hope that teachers can further transform their lives.”

Weselak operates a GoFundMe account on behalf of Pacifique’s organization. The funds raised go directly to supporting the children’s education. Those interested in donating may do so at www.gofundme.com/jw5p24

email: huff.record@outlook.com

Nancy Chicola • Dec 3, 2015 at 10:16 am

We can’t teach this stuff here. Teacher candidates and others need to form a deeper understanding of people around the globe in order to become effective global citizens. These international trips with a purpose are worth their weight in gold. Thank you for sharing your amazing experience in Rwanda.