The shale gas battle: Facts, emotion the top contenders

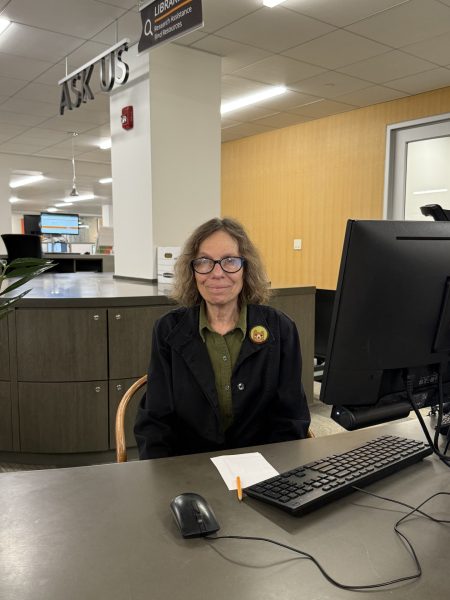

Photos courtesy of Patty Ceravole/NYPIRG

The Global Frackdown: Zombie Rally is held yearly in cities across the world and includes education and awareness events regarding fracking.

The town of Marcellus is said to be one of the most scenic regions of New York state. Known for its architecture, it is also home to a distinctive outcrop of shale that stretches almost entirely across the Pennsylvania-New York border. This is called, aptly, the Marcellus Shale, and it contains a reserve of natural gas that has remained untapped to this point.

Numerous towns, cities, and environmental protection and activist groups in the state want to keep it that way, despite mounting pressure and millions of dollars in lobbying from energy companies.

As of right now, the state has a moratorium on shale gas development, and individual towns have passed their own moratoria on gas companies coming in to drill. The purpose of these motions is to delay the process until there is more information on how the drilling process – hydraulic fracturing, or hydrofracking (commonly called “fracking”) – can affect a town’s economy, structure and environment.

For example, a moratorium was recently extended by a year on hydraulic fracturing in the town of Colden, about 35 minutes southeast of Buffalo, and a report was released on the potential effects it might have in the area. The report, compiled by the town’s four-member Hydrofracking Committee, cited noise levels, the impact of truck traffic on roads and the environmental hazards posed by the disposal of chemical wastes as reasons for the motion. Right now, they are one of 102 moratoria, 75 bans and 87 movements for prohibition in the state, according to FracTracker.org.

Patty Ceravole, the program coordinator for Buffalo State’s chapter of the New York Public Interest Research Group (NYPIRG), has been involved with the anti-fracking movement for four years, first as an employee for NYPIRG’s outreach campaign in the summer of 2010 and then directing its office the past three summers afterward in Buffalo, Syracuse and Rochester. According to her, anti-fracking groups have been outspent in Albany 30-1 on the issue, but for the last six years, they have managed to keep the industry at bay. NYPIRG and others have educated the public through canvassing and other events.

“It was really important especially toward the beginning of the campaign to make sure the community really understood the issue, because fracking can be a very complicated process to understand,” she said, sitting cross-legged on the floor of her office space. Written-on sheets of card stock surrounded her as she prepared for the Sleep-Out, NYPIRG’s annual event to raise awareness about homelessness. With a Sharpie in hand, she broke down the concerns regarding the “high-volume slick water horizontal hydraulic fracturing” that has begun to occur in other states.

Well bores are drilled vertically for thousands of feet, then turned horizontally. A cement casing is installed to serve as a conduit for a mixture of water and “fracking fluid,” a chemical mixture, at intense pressure that causes fractures in the shale formation and releases the natural gas trapped inside.

The controversy comes from the fact that some of the natural gas has been known to migrate into the drinking water these towns use. Dimock, Penn., is perhaps one of the most widely known examples, as documented in the Josh Fox film “Gasland.” The documentary is replete with images of residents lighting their tap water and freshwater on fire, which many believe is evidence of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, in the water supply. A 1987 Environmental Protection Agency report was recently unearthed which also cited groundwater contamination in Jackson County, W.Va.

Brad Gill, executive director of the Independent Oil and Gas Association of New York (IOGANY), a pro-hydraulic fracturing organization, said he has never heard of any contamination examples in New York State.

“We have wells in school areas, church areas, farms and vineyards,” Gill said, referring to the wells built in New York. “There have been no instances, which is really a testament to the regulations we have here in New York.”

There are also concerns over the chemicals used in the “fracking fluid,” which lubricates the well bores and helps cause the fractures. There are over 600 chemicals used in this fluid; about 200 of them are known at this point, as documented by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, and benzene and toluene – known carcinogens – are among the ingredients.

“The natural gas and oil industry is exempt from some really important federal legislation, which means they don’t have to release all of the chemicals they use,” Ceravole said.

The laws from which gas companies are exempt include the Safe Water Drinking Act, made possible by the “Halliburton loophole,” a piece of legislation included in the Energy Policy Act of 2005.

IOGANY says in the “Setting the Record Straight” page on its website that hydraulic fracturing “was never intended to be included in the legislation,” since it is not a disposal operation – that is, an operation that ensures solid waste is disposed of in an environmentally safe way.

Gill owns a company called Earth Energy Consultants, which provides consultations to members of the oil and gas industry. A petroleum geologist, he himself has been in the industry for over 34 years and is frustrated by the pushback and “misinformation” provided by anti-fracking groups.

“For someone to oppose hydraulic fracturing, they might as well say, ‘I am opposed to the development of American energy,’” Gill said via phone. “There are people – chefs against hydraulic fracturing who cook with natural gas. Their response is, ‘We’re not using fracked gas.’ But they are.”

As far as “Gasland” and documentaries like it are concerned, he said, “They are nothing more than movies. The industry has been able to easily pick them apart, taking it issue by issue.

“Those things aren’t done by those in the industry – they’re done by moviemakers. It’s real easy to instill fear in people.”

As for the safety of hydraulic fracturing, he said the process has become more technologically advanced and much safer. He also pointed to job growth, saying that the last numbers he saw on the topic said that 71 percent of the jobs in Pennsylvania related to the shale gas industry were local, full-time hirees.

But a report by the Multi-State Shale Research Collaborative, a collective of independent researchers across five states – New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia and West Virginia – dispute these claims, stating that the industry overstated its claims of job creation by nearly 17 times between 2008 and 2011.

The boom-and-bust nature of the industry also means instability in towns and counties that allow hydraulic fracturing, but Gill believes that can be said for any industry.

“And besides,” he added, “is it better never to have had that boom just because it’s going to end sometime? Look at all the people who don’t have jobs, especially in the Southern Tier. Across the border, there are people with brand new tractors and royalty payments.”

The truck traffic involved in drilling a well is another concern for Ceravole and those against hydraulic fracturing. As opposed to a vertical well, of which there are plenty in Colden and New York state in general, high-volume horizontal fracking requires nearly double the number of truck trips – more than 3,900 compared to around 1,800 for a vertical well. Hundreds of trucks, carrying millions of gallons of water and fracking fluid, can take a toll on the asphalt.

“The wear and tear on local roadways from one heavy drilling truck is estimated to equal the wear and tear caused by about 9,000 automobiles,” Colden’s Hydrofracking Committee wrote in its report.

Alex Bornemisza, a member of NYPIRG’s board of directors, and Ceravole have each seen the impact of thousands of trips back and forth on roads ill-equipped to deal with that much weight.

“It was hard to imagine that there was even a road there once,” Bornemisza said of the damage caused to one road in Pennsylvania leading to a well pad. He added that just the strips along the shoulders of the road where there was less impact from truck tires indicated that it was once paved.

“I didn’t feel safe driving on it in our van,” he said. “I can only imagine driving in a regular car.”

Gill says, however, that the process does not mean torn-up roads, citing that trucks don’t run on the roads during school bus times and that, in fact, companies have repaired the roads after creating the wells. According to him, multiple towns and counties have said the companies have treated the roads better than their respective departments of transportation.

He also said the water used in this process is much less than perceived, as gas companies recycle the waste water from wells, adding “x amount of freshwater” to it before sending it to the next well. Therefore, both the amount of freshwater used and the number of truck trips is fewer than stated.

“Critics point out the truck traffic as if construction on a 30-story building doesn’t create a lot of truck traffic, or putting up a wind turbine doesn’t cause that,” he said.

“Everyone feels that they’re right. Two people can hear the same information and interpret it differently. It’s emotion versus science, fact and track record – the industry provides the science, and the anti-fracking groups are based on emotion.”

So what would the alternative be?

Ceravole, an eternal optimist, believes high-volume hydraulic fracturing will stay out of the state. She said the government should focus on green energies, such as wind, solar and geothermal energy, but as of yet the industry has not grown enough.

“With the proper investments or improvements with the technology, we could definitely do it,” she said. “We could see them become sustainable. Instead of spending money on continued reliance on fossil fuels, we need to be reallocating money to these other technologies.”

Gill believes the state can’t sustain itself on green energy in the near future. Therefore, he holds his support firmly for the development of natural gas and voiced his disdain for the powers in Albany.

“It’s a shame, what Gov. Cuomo is letting this state miss out on,” he said. “What does Albany think they know so much more than 31 other states that are doing this? New York State is the only state able to produce its own oil and gas, and chooses not to.

“Contrary to what Cuomo says, we are most definitely not open for business.”

Email: [email protected]

Twitter: @A_Rodriguez39