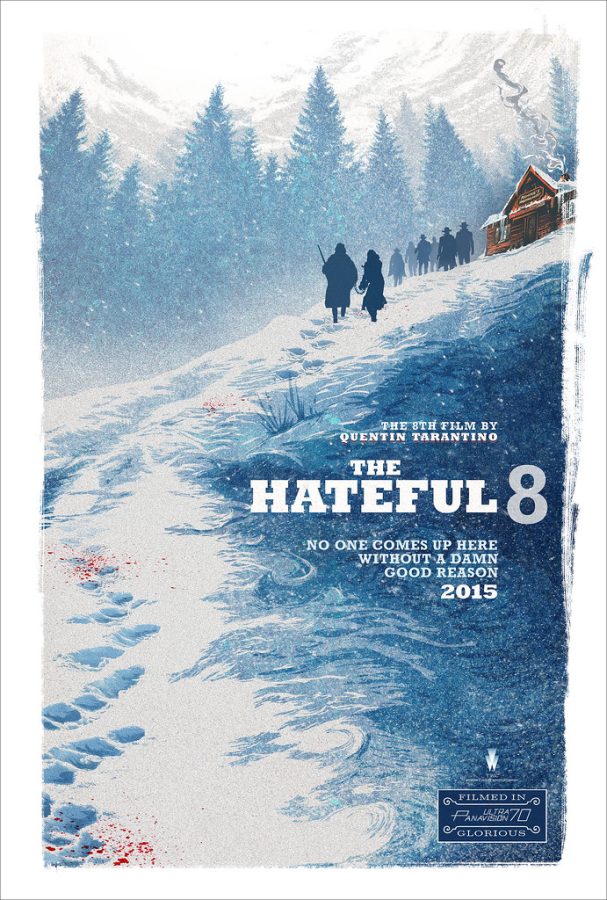

Revisiting: ‘The Hateful Eight’

December 27, 2021

The concept of unity is seen during tough times.

It doesn’t necessarily mean that people care for one another. There is no better example of this than in “The Hateful Eight.”

In the first scene, we see a statue of a crucified Jesus in the snowy landscape of Wyoming as the horse wagon of a bounty hunter and his prisoner mush past.

The brief allusion to Christianity sets us up as the principle of Christianity is opposite to the principle of justice. Justice offers the possibility of fairness, Christianity does not.

This film showcases the worst of everyone, even the characters who are supposed to be the heroes. They seem to be no better than the villain in the story, Daisy Domergue.

In the midst of layered characters, John Ruth is the fairest of all, and roughest of all, as well as the least intelligent of all.

Major Marquis Warren is the smartest, but manipulative.

Chris Mannix is obnoxious and racist, but inquisitive, which leads to an important moment in the movie.

Ruth treats the woman prisoner as violent and coarse as he would a male prisoner. He treats the Black Major Warren as an equal during post-Civil War, however there’s a debate whether or not it was his attributes that saved him from the blizzard or a shared humanity between two people.

When allowing Mannix on board to Minnie’s Haberdashery, saving him from the blizzard, a key point is Ruth does not keep Warren cuffed while Mannix demands his hands be free riding into Red Rock as he claims he’s the new sheriff.

When they arrive at Minnie’s Haberdashery, we’re introduced to a slew of characters whose intentions, we discover, are no good.

Everyone there is part of a criminal gang, waiting for their moment to rescue Daisy from the hangman’s rope.

They did not expect a Black man and future sheriff would be taking shelter in the haberdashery.

One of the criminals is Oswaldo Mobray/Pete Hicox, posing as the hangman for Red Rock, slated to hang Daisy when the snow clears.

In his monolog of Justice vs. Frontier Justice, Mobray explains the difference between the two, ultimately ending with the point that frontier justice, basically vigilante justice, is much more satisfying than the process of civilized justice, even when there’s a high chance of getting it wrong.

Things get hairy when we’re introduced to confederate general Sanford Smithers.

In the infamous monolog delivered by Warren, he describes how he killed the confederate general’s son as he was attempting to collect a bounty on Warren.

He kills the general as he was about to pick up the gun put there by Warren, supposedly provoking the general into shooting him.

When the general’s body falls, it knocks over the chess board in front of the fireplace.

I find this symbolic to Alexander the Great taking on the challenge of untying the Gordian Knot, or a more film-centric reference, “Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Ark.”

In Alexander’s case, the knot was complexly and intricately tied, and whoever could untie it would be declared ruler of Asia. One legend has it Alexander just cut the knot in half.

In “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” the assassin attempts to do a sword fight with Indiana Jones, Jones just shoots him, ending the battle in under a minute.

The complex problem of racism and capitalism, and the so-called task to break bread with people indifferent to the lives of millions of people due to the color of their skin, or their class, and the interwoven racism in the system was symbolically destroyed, proving that the best way to deal with a toxic ideology is to just destroy it, not feed it with compromise and strategy.

For the film’s finale we see the last remaining characters, Warren, Mannix and Domergue.

Domergue tries to bluff her way out of execution and tries to use racism to turn Mannix against Warren.

I find this parallels to the instances where a white woman can accuse a Black man of rape, and there was a time where they were automatically believed.

This was because Black men were seen as inherently dangerous and white men were trying to protect their women, not from being victimized, but from being with Black men.

An infamous example would be Emmet Till, a 14-year-old Black teenager accused of making a suggestive gesture toward a white woman. Soon after, he was kidnapped, and his body was mutilated, burned, then lynched. The white men accused were acquitted by an all white jury.

Mannix turns around and calls her bluff, not allowing racism to win.

Mannix and Warren together use their last moments of life to execute Domergue in the name of justice by hanging.

Mannix’s racism probably didn’t go away, and Warren’s indifference to Mannix was still there after coming together against Domergue. However, justice was served.

Quentin Tarantino’s technique for remixing film traditions and remaking them in his vision continues to be inadvertently socially conscious, and, above all, entertaining. The irony of such a large format film being used in such a limited space will always remain a major point of admiration for me.

In addition, the use of large format film to record such creative and graphic displays of hate, deceit, and crudeness is such a level of iconoclasm I can’t even fathom; this is considering the fact that 65mm film on Ultra Panavision has historically been used for epics that were safe and inspirational.

Inaccurate biblical epics, such as “Ben-Hur” or jingoistic pictures, like “How the West Was Won ” are what largely make up what this was used for.

I find this revisionist western a form of poetic justice for the groups misrepresented on a massive scale as this film throws away any notion of redemption or hammy morality typically found in epics.

This film is honest about its characters and subject matter, and its symbolism of the reality of the post-Civil War United States.

It was a tense and polarizing time, as everyone’s actions and beliefs during the war are now reflected upon.

What’s left are the people, whose lives were defined by this war. This war remains the deadliest conflict the United States was engaged in, and it was against ourselves.