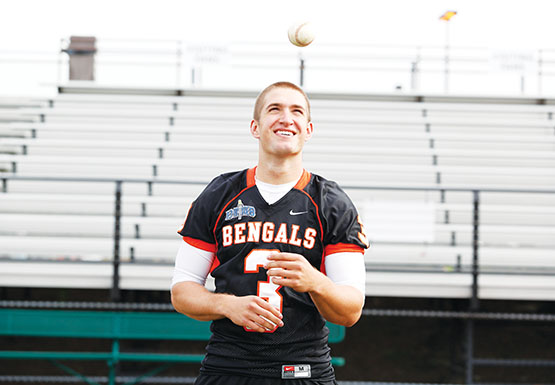

Hoppy returns to gridiron after ‘minor’ detour

When the Buffalo State football team travelled to Salisbury University for an Oct. 12 game, Kyle Hoppy was conversant with the area, but not so much with the position, he was in.

He knew Salisbury was a mid-sized city along the eastern shore of Maryland. He knew the best spots to grab a bite to eat.

He knew about the community’s affinity for the local baseball team — a substantial water tower, which includes a painted giant-beaked white bird with “HOME OF THE DELMARVA SHOEBIRDS” in black text beneath it, greets visitors to the city. The Shoebirds are a Single-A affiliate of Major League Baseball’s Baltimore Orioles and they play their home games in the nearby small town of Delmar.

For the better part of two months in 2012, from April to June, Hoppy called Salisbury home, living in an apartment near the university while playing for the Shoebirds.

Delmar was Hoppy’s penultimate stop on the road in minor league baseball. At the conclusion of the 2012 season, he stopped his pursuit of a lifelong dream of making it to the majors, which ultimately led to his homecoming in Salisbury.

Drafted in the 28th round of the MLB First-Year Player Draft in June of 2009 by the Baltimore Orioles as an outfielder, Hoppy played four seasons of minor league baseball before returning to the gridiron this year for the first time since his senior season at Orchard Park High School, in 2008.

Hoppy, 22, is a freshman quarterback for the Bengals and prioritized the present over the past, not thinking much about his fond time as a Shoebird, while in Salisbury a week-and-a-half ago.

“I’m in full football mode now and that’s the way I have to be,” Hoppy said.

•••

Buffalo State coach Jerry Boyes knew all about Hoppy.

In the fall of 2008, Boyes made a trip to Orchard Park to speak with potential recruits, but knew there wasn’t much use in talking to the Quakers’ senior quarterback.

Hoppy’s exploits in football at Orchard Park were well documented. His legs were just as potent a threat as his arm was, if not more so. He would go on to lead the Quakers to a state title that season while sharing the honor of being named Western New York’s top quarterback with current Bengals’ starting quarterback Casey Kacz, who starred at Sweet Home during the same time.

Still, Hoppy the baseball player garnered even more attention.

Although it wasn’t his senior season of baseball just yet, Boyes heard he was being recruited by Division I baseball programs, prompting the belief that college football was not imminent for Hoppy. His trip to Orchard Park that time was not landing Boyes the 5-foot, 11-inch lefty.

•••

Jim Gibson saw stardom in Hoppy from a young age.

In the summer of 2004, Hoppy had just finished seventh grade and attended a hitting clinic run by Gibson, who has spent 33 years coaching baseball at Orchard Park either on the JV or varsity level. A video camera surveyed all of the young attendees’ swings, allowing for Gibson to analyze and provide constructive feedback. Gibson would tweak aspects of a swing where he felt was suitable.

There was one unmistakable swing at the clinic that needed no alteration, and Gibson was insistent that the owner of it, Hoppy, not allow anyone to adjust it. That day was the first time Gibson met Hoppy, and he was watching a player who would entice a swarm of professional scouts to Orchard Park just five years later.

“It was just a flawless swing, it was just perfect,” Gibson said. “And he kept that swing all the way through.”

Hoppy was a contact hitter in high school, one who could consistently spray the ball to all fields. It’s a principle he embraced since he was 10 years old, leading to getting called up to play with Gibson and the varsity team for sectionals his freshman year, contributing to a squad that went to the state quarterfinals.

By his junior year, Hoppy was a star center fielder and captain of the varsity team. When his time as a Quaker was through, Hoppy held most of the school’s major offensive records like hits and home runs in a career, which were formerly held by former Philadelphia Phillies All-Star Dave Hollins, who played at Orchard Park in the early 1980s.

“He just was the model athlete, the guy that they make movies about,” Gibson said of Hoppy. “And the guy that just did everything right, from his school work to everything he did. Just a super kid to coach.”

•••

Not a game passed during Hoppy’s senior campaign at Orchard Park that a scout wasn’t present for after he was put on the radar two months before the season started. On National Signing Day, Feb. 4, Hoppy inked his acceptance to Bucknell University, where he’d have the opportunity to play both Division I FCS football and Division I baseball.

Hoppy reacted admirably to the pressure of being watched intently by scouts and was named 2009 Western New York Player of the Year

“It never seemed to affect him in any way,” Gibson said of Hoppy playing in front of MLB talent evaluators. “He just was always even keel and did a great job with that.”

During spring training in Florida prior to the 2009 season, Hoppy experienced his first interaction with a scout. A day after, he spoke with three more, and with any foresight, Hoppy would know a major decision was looming.

He learned of scouts’ forthright nature of critiquing a potential draft pick. Scouts in Florida told him to work on his throwing accuracy from the outfield and to develop a one-hop throw in order to augment his chances of getting drafted.

“They’ll definitely tell you what they think you need to work on, which I thought was great — something that you could always look to do before you actually do get drafted,” Hoppy said.

The Orioles’ scouting department vested the most interest in Hoppy of any organization, and even hosted him for a pre-draft workout at Oriole Park at Camden Yards.

•••

There is a stark contrast between Hoppy’s place on Buffalo State’s depth chart and Orchard Park’s during his high school days. He’s behind Kacz, a senior who has known Hoppy since high school through quarterback camps, and junior Dave Jacobs.

Coming back in August after a five-year layoff from football has been an adjustment for Hoppy. But with each passing day, his confidence grows as the skill that once brought Orchard Park a state championship becomes more evident.

“Being away for five years was a tough transition but I feel like I’m getting back into it now,” Hoppy said. “It’s coming back to me and I’m looking forward to the next three years of getting better.”

Kacz said while the football mechanics were rusty early on for Hoppy, there was continuity from high school in terms of football IQ as he has picked up the playbook and the offense rapidly.

Now, with two months of practice time, it looks as if the conversion was seamless for Hoppy.

“There’s been a couple times when he’s rifled some balls in there, it’s like ‘Wow, he’s got a cannon,’” Kacz said. “You can see how he played professional baseball because he slings the ball pretty good.”

•••

On June 10, 2009, Hoppy was getting ready for a summer league baseball game while his mom was sitting down, listening to the MLB draft, loud enough for Hoppy to hear in another room. And then, they thought it happened.

The Pittsburgh Pirates, with the 835th overall pick, make their selection.

Kyle Hooper.

“We thought it was me,” Hoppy said.

It could have easily been deciphered as a butchering of Hoppy’s name, but he and his mom found out less than a minute later it was not. The subsequent pick, Baltimore selected Hoppy, at the time making him the first position player from Western New York since 1999 to be drafted.

That August, Hoppy decided to withdraw his commitment to Bucknell. Being afforded the rare opportunity to play professional baseball, no matter the long odds of making it to MLB, was too much to pass up.

“The feeling of it was incredible,” Hoppy said of being drafted. “I had to make the decision on whether or not to go to school or go try and do what I’ve wanted to do ever since I was a little kid, and I decided to go play.”

Hoppy played for three different levels of Single A, the highest being with Delmarva. He grew an appreciation for baseball life on the road, travelling to mostly small towns along the east coast, as far south as Georgia, all the way up to the northernmost part of Vermont, seeing a passion among the locals.

“It’s interesting to see all the different landscapes and views and types of people in all these different towns that you go to,” Hoppy said. “They’re all fans in their own and I notice that the town the minor league team is in is pretty beloved by those people in that town.”

Adding to the unmatched experience of pro baseball for Hoppy was playing with and against MLB stars. The former outfielder played on the same spring training team as Orioles’ All-Star third baseman Manny Machado in 2011. He also took spring-training hacks against All-Star hurlers getting extra work in.

Hoppy remembers once singling off Josh Beckett, the 2003 World Series MVP, while struggling against Tampa Bay Rays ace Matt Moore.

“That was a little bit surreal — you’re playing the guys that are on TV every night,” Hoppy said. “You’re pretty much almost there, it’s just that fine line. It’s also a pretty thick line.”

A month after being released by Delmarva on June 13, 2012, the Philadelphia Phillies signed Hoppy. He finished the year with one of their Single-A affiliates, the Williamsport (Pa.) Crosscutters, before calling it a baseball career last September.

•••

Garrett McLaughlin was a high school football teammate of Hoppy’s, and currently coaches safeties for Buffalo State. In late February, while at a coaching clinic, an Orchard Park football assistant coach, Chuck Senn, relayed to McLaughlin that Hoppy had an appetent to come back to football.

With that knowledge, McLaughlin reached out to Hoppy in March. The two had several conversations about reuniting at Buffalo State, and Hoppy was enthralled enough to give Boyes a call, setting up a meeting in Boyes’ Buckham Hall office about coming back.

Each party expressed mutual interest during the April face-to-face. Boyes, adamant about recruiting men of character, laid out his vision for the program, and Hoppy wanted to be part of the plans.

“I really liked what he had to say,” Hoppy said. “I believe in what he’s trying to do here.”

Hoppy weighed his school options meticulously in the coming months — also considering UB, Colgate, Fordham and again Bucknell — until ultimately deciding on enrolling at Buffalo State in July, a month before training camp began.

Hoppy is in unchartered territory on game days now, holding a clipboard while learning the offense second-hand. However, Boyes sees potential in Hoppy taking over as the top signal-caller someday, and he will compete with Jacobs for the starting gig next season.

Though Hoppy admits learning from a distance this year has been beneficial, Boyes has seen enough from him in practice to warrant expectation.

“I think he’s embraced it,” Boyes said of Hoppy’s backup role. “I hope he doesn’t like it.”

•••

It was a rainy Buffalo afternoon on Sept. 21. The Bengals were squaring off with perennial national power Wisconsin-Whitewater. And with the Warhawks up, 52-7, Hoppy entered the game with 9:11 left in the third quarter for his first game action since 2008.

He went 0 for 3 on two drives, but the importance of the situation wasn’t measured in playmaking.

On Hoppy’s second play, an incompletion to Ryan Carney, he was hit so hard that his chin strap ended up more near his nose than its intended area of protection, and his helmet swung so far back it was covering more his neck than his head.

“‘I can’t feel my face,’” Hoppy told Kacz as he walked off the field after that drive.

It was a pertinent welcome back to football for Hoppy, a necessary step toward regaining the form he once had, which could loom large for the next three years of an improving program.

“Not getting hit for five years, I feel that needed to happen,” Hoppy said. “After that, I felt more comfortable.”

More akin to a collegiate hockey freshman than conventional college football rookie, Hoppy, though fortunate to have chased a major league dream, is basking in the present.

“There’s nothing like football,” Hoppy said.