The slow burn is old school, but still effective in cinema

March 9, 2016

In grade school English, we are taught different approaches to writing. You could start a narrative by jumping right into the action, which is great for a more exiting, fast-paced story.

The opening shot of “Star Wars: A New Hope” with Princess Leia’s ship, the Tantive IV, being chased across space by a Star Destroyer became one of the most iconic shots in cinematic history. It had the audience jumping from the get-go; a great opening to an iconic series.

There’s another approach that I believe is underappreciated, however. This approach is the slow burn. Setting the scene.

The slow burn makes me think of the old noir films of the 1940’s and 1950’s, back in a time when movies and television didn’t have the benefit of CGI, and Michael Bay wasn’t making everything go boom.

The story played out slowly, but built upon its characters and themes to the point where, at the end of the film, the audience is fully immersed.

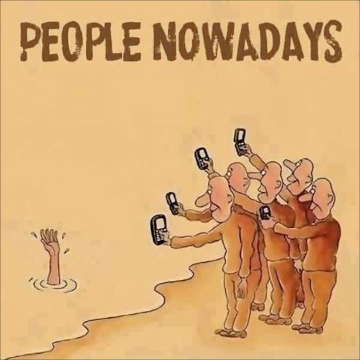

Our media caters to the nature of the times, and in 2016, we have become more and more adjusted to the notion of instant gratification. Our technology and lifestyles have made it difficult for us to want to wait for anything.

This has factored into why the slow approach in movies and television isn’t used as regularly as before. The best modern example in the difference between instant gratification and a slow burning narrative can best be seen in comic book movies and shows.

“Deadpool” swung right into the action, starting the audience off in the middle of the narrative. Lost in the action and excitement of the movie however, was a slow paced and brilliantly done origin story. It took the time to establish the lead’s personality, wants, and fears.

When the film was done, we knew what made Wade Wilson tick, and how he became the anti-superhero merc-with-a-mouth that we have all grown to love. It wasn’t shoved in our face.

An example of the fast-paced action style done wrong was in “The Avengers: Age of Ultron.” The film tried to throw a bunch of things at the audience but didn’t let some details play out enough. For example, all of a sudden Black Widow and the Hulk had a love interest that was completely absent from the first film. This detail came out of nowhere and was not elaborated upon; they just liked each other now, apparently.

Hawkeye had a secret family no one knew about. This detail came out of left field, and was not hinted at in the characters actions and tendencies at all. Sometimes it’s okay to elaborate on

details in a story. Sometimes it’s okay to be more subtle. Throwing things at the audience isn’t always the best way of going about a narrative.

The slow burn approach has been used extremely effectively in the Netflix Marvel Universe with “Daredevil” and “Jessica Jones.” The shows don’t just give away all the information right away. In fact, the main antagonist of “Daredevil,” Vincent Donofrio’s Kingpin, has had layers of his persona stripped away little pieces at a time. We don’t really know his full plans for New York City, they’ve actually been presented in a very vague way.

This makes the viewer want to come back for more. Details of Jessica Jones’ back story are presented in bits and pieces as well. It gives enough to make the viewer question what Jessica is all about and why she “doesn’t do the whole superhero thing.”

Matt Murdock’s (a.k.a. Daredevil) powers aren’t fully explained right away. His best friend Foggy Nelson has always thought of Matt being blind and frail, when in reality he has all of his other senses heightened. He sees a “world on fire” which allows him to be the super agile, strong and quick hero that he has become.

This was explained in a subtle way near the second half of season one of the show when Foggy figures out that Matt has been playing a vigilante at night. Matt finally explains all of this, which he has kept a secret from his best friend for years.

This important detail is given in a subtle, organic way, rather than being immediately given and smothered in the viewers face, the way it was when the character was played by Ben Affleck in the 2003 cinematic telling of “Daredevil.”

My advice for viewing anything is to let the story shape up. Give a show a chance to play out before deciding to end your involvement.

Sometimes, slow beginnings can create the best endings of them all.

email: [email protected]